Billy Dee Williams: The Radical Glimmer of Our Greatest Matinee Idol (part 2)

by Dennis Leroy Kangalee

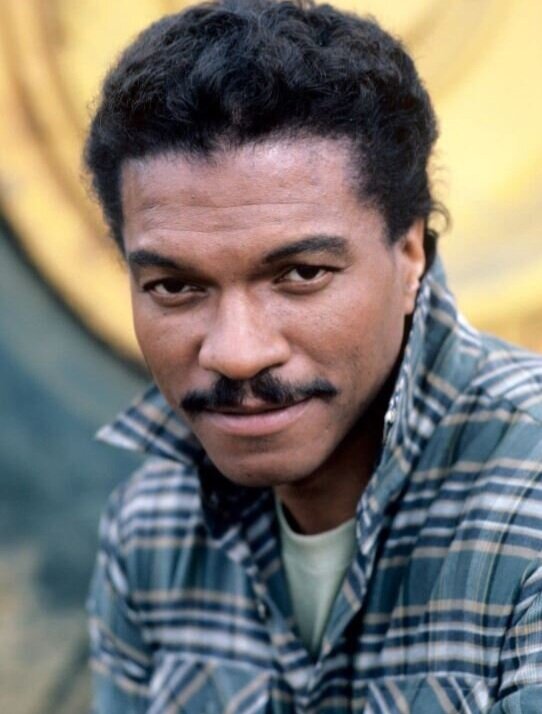

Billy Dee Williams as Brady Lloyd in ABC’s “Dynasty” (Aaron Spelling Productions)

MIND EXPANSION, REALITY, & PERSONA

“LSD saved my life,” says Williams, who’s otherwise firmly anti-drug. “I wasn’t doing it to get high. It let me get inside of myself. ”

One wonders if underrated celebrities or talented actors like Billy Dee Williams or Cary Grant, are not “taken seriously” by the power brokers of their time or the cinephiles who re-wrote the lexicon of the countercultural “Easy Rider, Raging Bull” Hollywood legacy because of their insistent maneuvering outside the box. Both Grant and Williams were devotees of psychedelic experience, something only Dennis Hopper and Peter Fonda’s tribe of rebel hippies seem to get away with. In some ways the middle-class comforts Williams and Grant attained early on offended the bad-boy white hippies who were pathologically wired to hold old world style in contempt as if it implied the racist and oppressive values of their own ancestors. Tsk, tsk…

This same generation also chastised Cassavetes for being concerned about middle class couples. It was Cassavetes who proved himself the far more radical than the Easy Riders, and Billy Dee had nothing to prove; Black people have a different relationship to “social standing” than whites. Having money and comforts doesn’t make you a sellout. It’s what you do with it that matters. Hopper eventually became a Republican and Peter Fonda (ahem) was always able to rebel because…his father had provided so well for him. A lot of the old-school actors and movie stars were not connected and did not come from well-heeled families. The image of Grant and Williams, debonair, from poor backgrounds – sophisticated Men – doing self-analysis through LSD is off putting and far too controversial for the “Hollywood” image their publicists offer.

Billy Dee Williams and Diana Ross (right) in “Lady Sings The Blues”

Getting psychedelic gave Williams a dimension into himself that allowed him to get in touch with what he possessed inside. The psychedelic generation had one thing over us all: the youth, activists, and artists of that age had serious interest in linking the spirit with the political and harboring realizations, no matter how difficult. The Mind-Expansive age was just that. And it was about self-exploration, getting inside oneself. Now it may be all about getting inside the White House or an Awards show or a museum. If the artists’ glow is dimming, think about how strange it is as well that celebrities – ever the vulgar combination of money, creativity, sex appeal, fashion, and civil rights – has dimmed and depressed us all. It might be unfair to blame Paris Hilton or Kanye West – but somewhere in there is the truth. These celebrities now and the heroes of the millennials don’t hold a tweet to the alarming charisma, intelligence and intellectual occupations of a Liz Taylor, Michael Jackson, Marlon Brando or Charlie Chaplin. Or a Harrison Ford.

Or…a Billy Dee Williams.

“I call my paintings ‘abstract reality…Sometimes I refer to them as ‘impressions/expression.’ It’s the best way I can explain them.”

“Louis McKay” 1994 acrylic on canvas on Masonite. National Gallery Museum, Smithsonian

There is a similarity to Billy Dee Williams’ on screen portraits and the paintings he does alone: both reveal an understanding of what THE IMAGE means and how it can be served to engage an idea or relay a way of thinking. Whether jazz musicians, the Tuskegee Airmen or himself – the face, the body, the person are iconicized in his portraits, “frozen forever” as they should be. But with a slight nervousness. As if a still life portrait had been made slightly agitated by a ray of strobe light. Caught in between something. Encased. As Lando says, referring to Solo in the Empire Strikes Back: “He’s alive…And in perfect hibernation.”

In a 2015 interview with Zoomer, en route to the Liss Gallery in Toronto where he was attending an exhibition of his own work, he declared that the cathartic process of painting was more fulfilling than “group” or film work – because its success relies on ones “own personal, private sensibility.”

The well-crafted Hollywood celebrity persona is not too far removed from a pop star’s self-creation (Bowie, Prince, Ice Cube – all self-made personas) which is not too far removed from the American myth of being able to start all over, remake oneself, create a new life, etc. Dylan’s dictum holds biblical reign: “He not busy being born is busy dying.” Where the average person is lucky to have one decent life under capitalism, the healthy notion of a second act is more attainable and within reach due to the changes of a Claude Brown or Tina Turner. Self-possession (“owning it,” as we say) is an indication of the conscientious labor Black America has put in to perceiving oneself differently and nothing other than what they desire to be.

The best known examples are so embedded in our consciousness we take them for granted: Cassius Clay conscientiously crafted himself as “the greatest,” becoming “Muhammad Ali” – as if he had spoken to Allah himself; Malcolm X underwent the most profound transformation that set the bar and now reads like cultural folklore: after prison gone was the world of “Little,” he was remade and owned by himself – his name bearing more meaning than any anthropological dig could reveal. Genetics and DNA become abstract concepts submarined into self-identification under the mask: My face, my name, my behavior bears all.

This personal iconography – either strategically formed or the result of traumatic transcendence – becomes both a sword and shield. For some, like actors who become cosmic celebrities – it becomes simply who you are. The face itself becomes like the boxing ring ballets of Ali or the speeches of Malcolm X. The only Black celebrity actor I feel who latched on to the notion of serious self-creation is Williams. Although not the greatest dramatic” character actor” (he never said he was) – Williams seamlessly fused the limits of his acting within the unlimited potential of his persona. Humphrey Bogart, Jimmy Stewart, Dick Powell - all did the same thing. In essence, he painted himself. And that is reality.

His painting of his alter-ego Louis McKay from Lady Sings the Blues handing Billie Holiday a gardenia is at the Smithsonian. One of many, Williams has at least 300 paintings in his catalog. Encouraged by psychedelic mainstay, artist Peter Max (check out his Beatles artwork from 1967-1968) Williams returned to his first love in the mid-80’s with gusto after having become disinterested and exasperated by all things Hollywood, I would imagine.

He carefully constructed and knew what he was doing by thoroughly embedding his persona via Louis McKay, gently pulling us into the center of his cobweb. It’s like the beginning of Papa Was a Rolling Stone. You don’t realize you’re deep in it until it is already underway. Billy Dee Williams the sex-symbol and the suave actor bolted out of Hollywood in a moment when Hollywood didn’t even know what to do with “a Black Sex symbol.” When he appeared on the screen in 1972, he brought all of Berry Gordy’s Motown acts’ swagger, suave, and sex appeal to the mainstream movie audiences in a dramatic role. I can’t underestimate how big of a deal that was.

It’s with his mustache that Williams eventually explodes as a celebrity, as if the facial hair brings more gravity, defanging some of his intensity, but turning up his sensuality and danger. The thin menace protruding behind the eyes, through the brow and along his jawline – is disarming and unmatched by anyone else at that time in Hollywood. Whereas most white actors looked ridiculous in mustaches in the seventies, Williams, and Pryor after him, owned and popularized the mustache and wore it like a badge of honor… or a custom-made three-piece suit.

REAGAN & THE EMPIRE

Billy Dee (middle) as Lando Calrissian in Star Wars: The Empire Strikes Back

I heard a story once that Irvin Kershner, who directed the 1980 The Empire Strikes Back, made sure to have the scenes between Han Solo and Lando Calrissian extremely short because George Lucas was nervous that Williams would usurp Ford’s charm on screen. I don’t believe this, but it is telling that their interactions are almost too short (in fact Lando’s entire arc in Empire seems like a rough cut of a teaser!) and Williams once joked that Ford would never be able to hold a candle to his charisma on screen.

Lando Calrissian (that name!!) was a new sort of character and phase for Billy Dee Williams – intergalactic suspense and sci-fi cool – and it could have been the ignition for a whole other foray into screen acting for Black movie stars who were damn good actors. (Strangely, under the conservative tide of the 1980’s – Ron O’Neal has his biggest screen challenge with the right-wing Red Dawn, where he plays the Russian Terrorist, Bela, with an accent Merryl Streep herself could not have done!) When offered the part, he loved that Lando was not written for any specific race or ethnicity; he was able to flex his imagination in the way George Lucas conceived. This roguish, sexy, gambler who ran his own city like a casino – as seductively entertaining it was on screen, it holds up better on the page unfortunately because we are denied more time with Lando. Had they cut 15 minutes from the opening of the film they could have devoted 5 or 6 minutes to Solo and Calrissian’s relationship. In any event, here’s a man who wears a cape, kisses women on the hand and lives in the clouds. What’s not to like? Forced to betray his friend (which Williams playfully always defended!), Lando redeems himself in the third installment. There has been much discussion and attention placed to the distilled “diversity and inclusion” of a Black man in Lucas Land, but I doubt that was any concerted effort, not that it should have been. Williams always felt he was offered the part because he was the best actor for it. And I agree.

In the 21st century re-imaginings and interpretations of such characters, Williams was supportive of Donald Glover’s interpretation but somewhat taken aback at the overly-conscious “black” appearance of Glover’s Lando – the informative Afrocentric hairstyle he felt was a bit off the mark and he is right: a Black actor should not have to be hemmed into what the White Gaze instructs and signals as being “black and proud.” This is where representation misses the mark and impedes artistry or expression. The Method actor experiences he doesn’t represent. A gross misconception amongst the “woke” generation and a problem that is destroying the singularity and funkiness of Black actors and their choices. Just because someone has kink or dreads don’t mean they’re down, dig? And quite frankly all the Black people we usually see in mainstream movies or TV are usually one of three types – as if that is the limit to our existence and as if representing one of these categories brings penance.

Williams found it disconcerting that it was implied in 2018’s Solo that Glover’s Lando was in love with an android as well. But we’ll leave that alone.

The original Lando Calrissian came of age as the United States, and the world following suit, got itself back on track from the 60’s hangover and the radical ideas that lingered through the seventies. How long could it all last? In some frightening way it makes that at the dusk of his greatest decade, Richard Pryor set himself on fire as screen actors of his generation found more creative ways, but no less destructive, to express the angst of the corporate imperialism rearing its head in full force. These actors reflected the turning of the tide in mainstream culture – avarice, ego, individual vs group, Hollywood versus neighborhood. Even the fab four of Hollywood male actors – DeNiro (Raging Bull), Pacino (Scarface), Hoffman (Tootsie), and Jack Nicholson (The Shining) turn in extraordinarily self-conscious and didactic performances that rebound Hollywood and America’s spiritual state in the 1980s.

It’s all there in the Empire Strikes Back, quite possibly the darkest children’s movie ever made. That Darth Vader wins, that the empire literally strikes back is astounding. The entire spirit of Reagan’s empire pervades the film in the way that it later overwhelms Harrison Ford’s character in Blade Runner, for example.

Empire is humorless for the most part and Lando Calrissian carries an anxiety with him, it’s obvious he is at the behest of Vader.

Williams even, somehow, telegraphs to the audience about what is occurring on screen as well as off. He has one eye in Cloud City and the other on us. Lando is the MODERN MAN. And he reveals himself to be far more honorable than we first believe…but the role is so trimmed down his depth never comes to realization. As if he’s the Spook in the clouds, he acts covertly and strategically to subvert Vader. The weight of evil capitalism on his shoulders, he acts out of survival and insecurity but not inured to regret or shame.

De Niro does this in Raging Bull. He gains as much weight as Pacino consumes cocaine in Scarface while Jack Nicholson in the Shining goes insane in the Overlook hotel…writing as much charisma as Williams contains and deflates as Lando Calrissian. The Reagan era. It infected everything and everyone.

But beneath that torrential rain, Williams still retained his soul and made some interesting excursions back into small art-films like his wonderful collaboration with John Cassavetes in Marvin & Tige, an exquisitely understated and unsentimental tearjerker. Their scenes are appropriately short, but it’s powerful to see them exchange energy and engage in nuanced and complex behavior. Another little-seen, forgotten hallmark of Williams’ work.

That two of the handsomest and most charismatic actors from the 1960’s emerged into the universe with their inimitable personas attached to George Lucas’ science-fiction western – is interesting. Both with steaming presence in their voices alone. But whereas James Earl Jones has always been inconsistent towards the notion of “black drama” and its legacy – especially some of the radical politics it spawned and embraced – Williams has never let his guard down. When Jones’ run as Troy in August Wilson’s Fences, ended it was Williams who continued it. This was the production I saw in 1988. All I remember is the oddity of seeing Lando emotionally bruised; Williams became real for me in that one role. Williams’ Troy was less ornery than Jones’ Biblical interpretation. Less Job, more Elijah. His Troy had less a chip on his shoulder and more of a profound sense of confusion if not depression, which in many ways makes that interpretation even more heartbreaking.

Floyd Webb, a Zelig-like character and landmark film programmer in Chicago (with hands in so many pots it would be difficult to discern who was cooking if this were a restaurant) has often reminded me that Williams was one of the only Black mega-celebrities with revolutionary inclinations who actually helped finance his own revolutionary movie in the early seventies and always, despite the myriad of changes and disappointments a bizarre place like Hollywood spins, remained true to the spirit of progressive thought, liberation politics, and the universe’s spiritual pull.

AN ACTOR IN SEARCH OF A DIRECTOR

(right) Billy Dee as D.A. Harvey Dent in Tim Burton’s Batman (1989); (left) the actor & character in comic book form in 2021’s “Batman ‘89”

He’s better in most movies than the movie itself; the struggle for the creative Movie Star is to have scripts that enable his persona, showcase his talent, and gently highlight his intellectual strengths. Williams seldom had that but there are countless movie stars who could say the same. What none could argue however is that Williams was the last of the Golden Age Hollywood Matinee Idol; “the black Clark Gable,” a thinking person’s seducer. Like Paul Newman and Marlon Brando twenty years earlier at the height of his sexual appeal his acting instincts were almost irrelevant, in the mid-1970’s Williams could simply do no wrong. Unlike pop-star actors like Brando and Newman, however, he was not tormented by any of the impositions of acting and while he could not incur the opportunities, scripts, or proclivities of those actors (who could?) he seemed to have always been at ease with his talent and the psychosis of Hollywood, but this is all due to his embracing of Jungian and Eastern philosophies.

Still, one can’t help but wonder what he would have done had he developed a series of works with an empathetic producer and director who was firmly on his level, willing to gamble financially, saw life as he did – or saw what possibilities he contained inside of himself that he was unaware of. He has said that he always wished he could have played in screwball comedies; his love for sophistication (note to millennials: sophistication is not bourgeois, it is an approach to life, not a pretense or status to be attained) always made him very aware of personal style, panache, appearances, and behavior. A perfect fantasy collaboration is him in the hands of an Ernst Lubitsch or Hitchcock. I always wonder what, if Brian de Palma in the 1970’s (who idolizes Hitchcock) could have done with Williams if he had the humorous insights that Hitchcock had and if his own work was more firmly progressive and less exploitative. (Blow Out would have been an incredible film with Billy instead of John Travolta, for example)

Or if he had teamed up with Peter Bogdanovich? That would have been a remarkable union. But we can safely assume there were no next level offers that could have guided him into the witty and adult romantic comedies of Woody Allen or Mike Nichols. (An even greater “what if” teams Williams with Kathleen Collins, the comedic Julie Dash in some ways, director of the brilliant “Losing Ground.” Black Narrative Directors of the 21st Century: do not miss these opportunities again. You have more agency than you think. If not imagination!)

It is the failure of the second wave of Black Hollywood directors, and my generation included, that we have not re-assembled and delved back into the legacy of a Billy Dee Williams to have impact or express an idea in a new way in our rabid devotion to movies. Lesser actors, from Travolta to Burt Reynolds to Brad Pitt, have had directors committed to their energy or personas –and help them go even deeper as actors, while holding their hands and unleashing a whole new energy onto the audience. I don’t particularly like those films but some of them are legitimate artistic excursions, despite what the results have reaped. Black filmmakers -writers, directors, producers – owe Billy Dee Williams and those akin to him a remarkably high debt. We don’t acknowledge or regard him the way we should. It’s easy for a Jordan Peele to exploit “Blackness” and racism amidst the corporatization of Black Lives Matter and the homogeneity of discussing “trauma” and “colonialism” in mainstream public forums. When Williams did the Final Comedown, he was not doing it cynically to exploit he was doing it as a pledge of allegiance to radical activism and the Blacks who gave their lives to the revolution. He was never a tourist nor a tool for White people who love anointing Black celebrities and now, filmmakers. The debt is high. It lingers even when many of us may never know it is there. And it’s possible it will never be paid. Certainly #Oscarsowhite is no excuse, nor is the disintegration of American soul art and entertainment. In fact, as we sink – that should be the warning sign!

With the world continuing to make fodder out of everything, with our media ecology lapsing into decadence, it would be fantastic if the silver screen could give us Black Hollywood Stars with the depth, dignity, and political fortitude of Billy Dee Williams.

The answer is not in the stars, but ourselves. And we shall be underlings if personas are owned by behemoths like Disney – and feel like they are such.

We pretend that numerous actors are “the next Denzel” or that simply because something or someone is “Black and handsome” and quite possibly talented - that they hold the key or sip from the chalice of Hollywood authority.

The chalice exists but it has nothing to do with Hollywood. Hollywood didn’t make Billy Dee Williams; it could only exploit him. He was never owned.