A Review of RUSTIN, pt. I

by Dennis Leroy Kangalee

The Complexity, Gravity and Dimension of Organizer and Visionary Bayard Rustin is Derogated in the Obamas Sensational and Shoddily Made Movie about the Architect of the 1963 March on Washington

This still from George C. Wolfe’s Obama-backed “Rustin” looks less like a frame from a movie and more like an advert at a bus stand for ‘Equity & Inclusion.’ And it imbues the entire feeling of the movie: colorful, shallow, empty. If only the drama was as scintillating as the over-lit movie. Wolfe seemed to think he was making a confectionery instead of a docudrama.

*

Many things have been written about this Disneyfied movie inspired by the life and early activism of outsider, labor activist and Black civil rights organizer Bayard Rustin. While some choose to jump on the Neo-Liberal bandwagon of the Obamas (their production company Higher Ground produced it) preferring to honor the competence of Colman Domingo’s acting prowess in hopes of him being an Oscar contender (as if that means anything), others have rightly taken the film’s politics to task, noting that the movie is simply a homogenized cheerleader peddling and patronizing LGBTQ identity-politics as opposed to expressing or telling us about the intrepid Leftist radicalism of Rustin’s identity.

While I have been an outsider to the formal world of the performing arts and activism, yet deeply entrenched in theater and radical politics (so much so that it has often confused, alienated and confounded some) I shall do my best to approach this autopsy by mentioning things others haven’t especially criticized as it pertains to what it actually is – a movie – and to the politics “outside” what the film purports to show.

While the movie deals with Bayard Rustin’s activism at a certain moment in his life, and all of us, for better or worse change (or should!) and have different periods, the underlying image of Rustin is that he was simply a brilliant civil rights activist maligned only because he was gay and that in and of itself made him an outsider. No. You’re an outsider if you march to the beat of your own drum. And you’re destined to be an outsider forever if no group, or persons, or tribe, or idea claim you. And while outsider is an apt adjective to describe Rustin to some degree (the Singer-Kates 2003 documentary Brother Outsider is a worthy film on Rustin, getting closer to the spirit of who and what he may have really been), it is misleading in many ways as well. Because, unfortunately, some of the disturbing views Rustin held in the second half of his life brought him closer to the center of the conservative’s inner-sanctum. Deeming him an “insider” in a strange way of the hegemony put upon us via the culture wars.

I shall delve deeper into that in the second part of this essay. This journey has been a labyrinthine and exhausting one. As if I myself had slowly made notes on a film on a film about Rustin that I could never bring myself to make. So, what I have in front of me is a collision of articles, facts, notes, archival footage, interviews – but mainly a cozy big-budget movie that aims to tickle instead of teach. I shall try my best to perform this post-mortem with my stock and trade as a radical artist employing visual liberation and as a member of the radical Left concerned about how Hollywood chooses to co-opt, distort, ignore, and present important facts that should be carefully tendered when relayed on screen. Let’s get right to it.

Aesthetics, Performance, Politics: The Canvas of a Director

In George C. Wolfe’s Netflix movie, Bayard Rustin comes off like an overwhelming and precocious teenager, full of nerve but no real verve. He organizes, he sings, he parties, all while masterminding one of the hallmarks of the 20th century’s human rights events and yet…it all seems so fey and pat. You don’t get a sense of how complicated he really was: critical of communism, but a massive Labor activist and supporter of unions; an extreme disciple of Indian lawyer/activist Mahatma Gandhi, who it was later revealed, reviled Blacks in Africa, the poor, and was grossly misogynistic. Rustin, like King, was not around to witness the re-assessment of Gandhi’s contemptuous views that later revealed itself at the turn of the 21st century – it was well known amongst activists and intellectuals who did not believe in sacred cows that Gandhi was vehemently racist against Blacks and despised the “untouchables” in India. And while Rustin was correct about being dismayed with Paul Robeson’s blind admiration for Stalin, he himself would have to have faced up to the piper on his devotion to Gandhi. One doesn’t even have to read the fantastic Arundhati Roy book, The Doctor & The Saint to digest all this – a mere glance now at mainstream publications delve into this, however shallow. NPR dissected Gandhi’s terrible hypocrisies in 2019. Now, Rustin has been long dead but it’s the job of the filmmaker to illuminate ideas that have in the end conflicted with their subject’s own sense morality. This is why biopics are incredibly frustrating. They simplify and flatten, instead of distilling, a person’s character and what drives them.

The direction of the film is a nightmare. Which is to say that the movie does not even succeed as compelling drama.

The awkward dialogue written by Julian Breece and Dustin Lance Black (who’s wit and edge for Gus Van Sant’s excellent Milk never infers itself in this movie) and exists on the screen as mildly goofy and snarky “civil rights” dialogue that Black and Breece probably had some fun with – stuffing dialogue with facts and resumes about all the characters and then free-falling into dalliances with Rustin’s gayness implying the general “angst” at finding the right love of his life (blah-blah-blah). One of the greatest sins of the script is the cliché of the fictional closeted pastor who indulges in a quick affair with Rustin. (We will explore more of the script’s problems in the next installment of this review. The 1990’s sitcom Family Matters suffered in a myriad of ways from white writers “writing for” a Black TV family. Rustin suffers the same conundrum, but it is worse because he is a real human being; a galvanizing and brilliant individual who deserved at a least a script as sophisticated and imaginative as he was. The writers wouldn’t necessarily have had to have been Black. But they should be from the movement. From some wing of the Peace Movement, organizing movement, anti-racism movement – formally. It should have to go beyond Civil Rights’ which everyone on Earth thinks they are an expert on.)

Factual or not –if the artistry itself is lackluster , who cares? Doesn’t matter if you get someone’s accent right if you don’t believe in anything you are saying or…if there is no danger. As dynamic as the plot is, there is no sense of urgency and no sense of risk. It’s all too smug. “Yes, we know this happened and that, see how smart I am?”

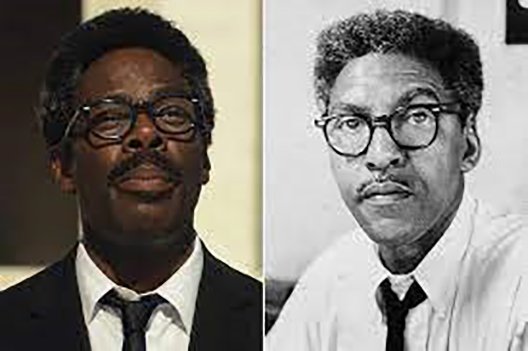

Bayard Rustin in 1963 (photo: Warren K. Leffler). The depth of his eyes never come through in Wolfe’s movie.

George C. Wolfe exhibits Colman Domingo as less a political thinker and activist than a gay flame who burns with desire to tiptoe like a dandy chipmunk holding Thoreau and Gandhi in one hand and Baptist passion and A. Philip Randolph in the other -- doing a Little Richard routine with a bad cold. Domingo’s physical quirks sometimes comes off as a man obsessed with smelling his upper lip – as if something was caught in his mustache. And this is all from the first five minutes of the movie.

Colman Domingo (L) and Bayard Rustin (R).

This is one of our great political organizers, thinkers and non-violent theorists?

*

George C. Wolfe is a towering figure of American Theater. His landmark productions of Jelly’s Last Jam, Bring in Da Noise, Bring in Da Funk, Angels in America, and Topdog-Underdog are phenomenal examples of commercial theater aspiring for art and sometimes succeeding. Wolfe re-defined the American musical in the 1990s as Jerome Robbins did in the 1960’s. Wolfe was a massive influence on my generation’s understanding of theater, what Broadway could be and how Black Americans could contribute and leave their mark on the well-heeled couture of America’s post-counterculture theater. Wolfe was from that counterculture, he is a baby-boomer who, like most our parents, saw the incredible changes in society and also witnessed incredible occurrences, once-in-a-lifetime moments. But Wolfe fails as a film director. And unfortunately, he is professional in all the worst ways, comfortable in all the annoying ways, and gives the impression that he’ll chase a dollar instead of a dream. A stage is where Wolfe can presume to understand and talk about life.

Behind a camera, Wolfe not only fails to express anything interesting he fails to bear witness. So, he exploits and does what most network and studio directors (and now, since the dawn of this century, most moviemakers) do: pander, mug and ridicule. And if an idea or moment is too heavy, or dare I say “tragic,” the directors – having no desire to plumb any kind of depth – sit back and just try to “have a good time.” As a theater artist who came late to film, I can relate to Wolfe in many ways. I defer much more to spatial expression of bodies than to the vocabulary offered to me in long and wide-angle lenses. The difference is that I always recognized my cinematic limitations and turned them into assets; you gauge the real ability of an artist, critically, in what it is they don’t do well – traditionally -- in a given medium. (Just look at how punk rock and hip-hop developed.) It’s how we are able to appreciate the singularity of artists like Melvin Van Peebles or Wendell Harris or Orson Welles who never used cinema in a “traditional” way. Because they simply weren’t wired that way and…they were less devotees of music than composers who had something to say through notes and chords. Some of our greatest theater directors have made wonderful films and have no problem vacillating between the two. Some are geniuses like Bergman or Peter Brook. And some are charlatans cashing in on identity politics, Civil Rights Movement history, or their own “Blackness.” This is not equating Wolfe’s terrible films to exploitation flicks, possibly his are worse. Because his films, especially as of late, pretend to be something that they are not.

As he did previously with August Wilson’s Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom (a catastrophe I will never recover from) it’s evident that Wolfe’s directorial sins include dismissing the gravity and drama of emotion or ideas itself – as they could be rendered tonally on screen in favor of false levity surrounding just about everything (the lighting in the film is one of the movie’s major problems, we’ll come back to this later). There is a laissez-faire rendering of the political climate of the late 50’s-early 60’s, and an incongruous ironic thrust against Rustin’s revolutionary urgency expressed with a looping jazz score – all which seem to sound like a third-rate Elmer Bernstein score. A personal request to any filmmakers reading: stop using jazz for soundtracks. Respect it, leave it alone.

If classical music has lapsed into muzak and schmaltz, the use of Black American classical music or “jazz” has become so perfunctory in movies dealing with civil rights or “Black themes,” that it lends itself to the ubiquity of nothingness that pop & American culture, specifically, right now represent. The music is not being used in an interesting way, it’s as if anyone could have decided to use it. Its employment is less an artistic choice than it is lazy one. As if the music team rolled their eyes at 2AM and said, “Oh no, we have to score this??” and then after several joints, they decided to just go with the easiest, most cliched sound and choice: underscoring a moment or two as if scoring a cartoon or a madcap late 1960s TV show. It is embarrassing and follows the tropes from the establishment’s Film Class 101. It gets worse in Rustin when Coretta Scott King sings “This Little Light of Mine” in the kitchen! If these choices are to be considered if ‘Only Blacks can direct Black Stories’ – and it should be considered because it falls under the director’s reign – then it does nothing for the defense and only empowers the prosecution. (In fact, I am in court now and there is no defense. I think they’re across the street getting drunk. Oy vey. And the band played on…)

Wolfe was once known as a keen director of actors in theater, he knew how to utilize them if not necessarily inspire them. Yet in each of his films, however, he seems to get more and more insecure and exasperated by the very idea of actual honing a performance. His winsome framing of Colman Domingo as Rustin is cute and then annoying and it does nothing for the film and every other actor/character suffers on screen. Why in the world would Wolfe do this? I don’t believe it was an aesthetic choice, I believe it was more of a political one. But this implies that he knowingly presented his character as shallow, stuffed, and phony as they look on screen. But, as the director, didn’t he?

Sometimes you don’t know what to think. Sometimes all you are looking at is someone collecting a paycheck. If that’s the case I prefer to watch the construction workers outside my window. They are more honest.

Wolfe’s filmmaking and showing of Bayard Rustin’s political and personal life registers as cynical and uncaring. I don’t care who it is, at the end of the day a film performance is the result of the Holy Trinity of cinema: the director, the cinematographer, and the editor. Why? Because where a stage director puts psychology into behavior and then passes the baton along to the actor – making them a co-conspirator – in the literal presentation itself – in movies, the director “captures” a performance. And then they present it.

And that particular POV is what Peter Brook bemoaned he couldn’t ever shake off from behind the camera is the defining difference. While a play could be cubistic, lending itself to multiple viewpoints as its actually happening – film is not only literally flat like a painting canvas, but also metabolized through one person’s ultimate perception: the director. An ensemble in theater and dance and music can work together and achieve a cosmic consciousness and become “one” singular style or “author” but there is an agreement. If theater is a mutual partnership in some way – like a great elopement, then film is an arranged marriage. And sometimes it is not always a happy one.

I am mining this problem thoroughly because this is a film publication and because directing is, I still believe, an art form. One in need of a real reassessment and dialectical engagement. I despise intellectual games and pretense in the arts, but there is a time and place for ideas, practices, and beliefs to be discussed. To simply “make a movie” nowadays, for example, is riddled in ideological politics. The great theater director Lloyd Richards, famous for his staging of August Wilson’s plays, once remarked that to say that you are not political is in itself a political choice. And there is an ominousness today when we discuss ideas, politics or that other frightful word the right-wing have bastardized: morality. George C. Wolfe was endowed with a comfy budget, a hotline to Michelle Obama on Sundays I am sure, and a historical figure we are likely to never see again. And while he partied with the ingredients of Hollyweird moviemaking (“people shaming” as some call it) and Rustin’s life, pandering to Black audiences and the theatrical establishment and the salivating smug Liberals of both coasts, we lose Palestinian poets like Refaat Alareer in Gaza. This has to be contextualized. Everything we do now as artists and entertainers (yes!) must be brought out into the open and questioned. As Rustin took sides, so must we, no?

Does one not see that there is something irrevocably lost or abandoned and polarizing when mainstream production houses and avatars of the showbiz bourgeoisie are co-opting and reframing who they want Bayard Rustin to be and spending millions of dollars to do this, luxuriating in movie narcissism when resistance fighters, modern day revolutionaries and artists like Alareer are being killed? We have reached a zenith in navel-gazing biopics that are nothing but atrocious self-obsessed and congratulatory commercials or entry ways into the next level of Capitalism or rather, the American Circus. Both of which Rustin was critical of and sober enough to realize that both would destroy us if we didn’t take the fight against it seriously.

Like a good director himself, Rustin had to be less concerned with his own neurosis or obsessions – in favor of the text he was illuminating or the idea/feelings he needed to express. And if he was strategically composing some great text or play, then Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. was his inimitable and brilliant muse-actor. I would have at least appreciated the film if the dimensions of these two men’s relationship were plumbed, the yin and yang of civil rights strategy, the mirror reflections of the Black church, the blues spirit. The film should have explored this more. Two heavyweights of thought, of philosophy, of vision for Black Americans in a very specific moment. Instead, the movie has fun with the locker-room innuendos and inferences about MLK and Rustin’s homosexual affair. It is problematic in a multitude of ways.

*

An important post-script to chew on before I leave you if you have gotten this far:

My mention of poet Alareer is not an attempt to be clever or provocative. I am seriously concerned with where identity-politics and “Blackness” in the American circus is headed. To be “Black” is not a euphemism for “revolutionary” or “humanitarian” (it should be, however!).

President Obama awarded Rustin, posthumously, with the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 2013. It sounds curious, doesn’t it? Not really. President Reagan eulogized him in the aftermath of his death, stating, “We mourn the loss of Bayard Rustin, a great leader in the struggle for…human rights throughout the world… He was denounced by former friends, because he never gave up his conviction that minorities in America could…succeed based on their individual merit. But Mr. Rustin never gave an inch. Though a pacifist, he was a fighter to the finish.” Ouch. It’s nauseating. But you can see what has transpired with Bayard Rustin’s image and who controls it.

Despite his support of Jewish Zionism and Israel, I would like to think Rustin would be appalled at what became of Israel; how intrinsically racist and venomous it ultimately is. Like his confused and blind support of Gandhi. While The Obamas and Netflix want to present him as a “good, self-loving gay Black man who honored non-violence” in the early 1960’s, castrating him of any complex depth, I would want to portray him even deeper, get to the heart of the matter: focus on everything post-1963. How can a person claim to be a universal humanitarian and champion peace if they were staunch allies of Israel’s first Prime Minister Menachem Begin and the IDF? Perhaps, like Gandhi, he too was a possessor of “selective caring.” Someone once said that Rustin is human like any of us. But somehow these answers don’t sit well with me. I prefer to say “Great thinkers have even more complicated problems and deeper contradictions than their most original ideas.”

My own compass inside is telling me that Rustin couldn’t shake the desire to be “part of” the power structure. The only people he ever alienated were Black or Brown people who had been oppressed. It saddens me. But he deserves as complex a treatment as Eldridge Cleaver would, another fascinating and chameleon-like figure who felt eager to cozy up to Ronald Reagan as well in the 1980’s.

Our pacifist “angel” Bayard Rustin (L) and Menachem Begin, the first Prime Minister of Israel and avowed believer in violence (R) 1979. In middle is Robert Brown, vice-president of the National Urban League

Rustin admonished the Black Panthers communist leanings, militant resistance, and engagement with truth tellers who spoke about some of the insidious racism harbored against Blacks by Jews in America, for example.

I leave you with the full text of an open letter Rustin wrote to Black Americans in 1979, in the New York Times, clutching his pearls, trying to dissuade them from rightfully supporting Palestinian resistance and accusing the PLO as mere terrorists. (Interestingly enough, this is just one year after Vanessa Redgrave’s righteous public excoriation of Israel’s terrorism during the 1978 Academy Awards and her staunch advocacy for a Palestinian state.) It’s a lot to chew on. But necessary when we pick back up with the next installment focusing on the factual and political problems of Wolfe and the Obama’s “Rustin” movie.

Thanks for reading.

To Blacks: Condemn P.L.O. Terrorism

By Bayard Rustin – New York Times, Aug. 30, 1979

Amid the heated controversy following Andrew Young's resignation as the United States delegate to the United Nations, some black people have suddenly embraced the Palestine Liberation Organization.

As I see it, some black leaders have turned to the P.L.O. in an effort to act as conciliators between Israel and the Palestinians.

Other blacks, I believe, met the P.L.O. representatives in New York to demonstrate their independence from official United States policy.

And still others viewed such meetings as a way of striking back against Israel and the American Jewish community for their supposed involvement in engineering Mr. Young's ouster.

But regardless of motivation, I think black people must clearly understand the moral — yes, moral — issue involved here.

For in seriously considering links with a group like the P.L.O., the black community is moving beyond the realm of mundane “politics as usual.”

We are moving into an area where we face three enormous risks.

First, we risk causing serious divisions within our own ranks; second, we risk the forfeiture of our own moral prestige, which is based on a long and noble tradition of nonviolence; and third, we risk becoming the unwitting accomplices of an organization corn mitted to the bloody destruction of Israel —indeed of the Jewish people.

Some people have pointed to a few superficial parallels between the P.L.O. and American civil rights movement. Naturally, this talk about the P.L.O. as a “civil rights” group or a minority movement within Israel has generated sympathy for the Palestinians among black people. But this identification and even solidarity with the P.L.O. is based on a terrible perversion of the truth, not only the truth about the P.L.O. but the truth about our own movement as well.

Looking back on the history of the P.L.O., one thing has become abundantly clear: The P.L.O., from the day of its creation in 1964, has never once uttered a word in support of any form of nonviolent resistance, peaceful relations between Israelis and Palestinians, or a political solution to the complex problems in the Middle East.

By contrast, black leaders in America, especially central figures like Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and A. Philip Randolph, never once in the long history of the civil rights struggle countenanced violence or terrorism.

American civil rights leaders, of course, chose nonviolence for many political and tactical reasons, but Dr. King once identified the key source of the movement's strategy when he noted that the black American rejected physical force “because he believed that through physical force he could lose his soul.” In short, the choice of nonviolence was based on deeply‐held moral principles. It was based on a desire to build community, to unleash the creative force of love, and to protect and enhance the God-given human dignity of all people, be they friend or foe.

The P.L.O., however, espouses the opposites of all these principles.

In word but more importantly in deed it espouses violence, hatred and racism. It repeatedly scorns reconciliation. While Dr. King frequently spoke of nonviolence as “the sword that heals,” the P.L.O. exalts the sword that kills.

My description of the P.L.O. here no exaggeration. Its tactics, values and goals are candidly set forth in its national Covenant and other official documents. Its legacy of terrorism written in innocent blood across Israel and Western Europe, and even across the Arab lands of Jordan and Lebanon.

Between 1967 and 1977, for example the P.L.O. was directly responsible for killing over 1,100 unarmed men, women and children; its terrorist activities maimed nearly 2,500 people: and it held over 2,700 hostages. Moreover, this organization has trained and armed other terrorist groups such as the Baader‐Meinhof gang in West Germany and the Red Brigades in Italy.

Considering this record, I fear that individuals who see similarities between our struggle and the terror campaign of the P.L.O. are ignoring or twisting the facts.

By harshly criticizing the P.L.O., do not mean to suggest that black leaders have no business concerning themselves with Middle Eastern problems. Nor am I arguing that blacks should shun the P.L.O. so as to ingratiate themselves with American Jews. Rather, I am saying that if black Americans are to play any constructive or conciliatory role in shaping American policy in the Middle East, we must do so in a manner totally consistent with the moral and spiritual tradition of nonviolence.

We must therefore reject hasty and expedient moves; we must reject any formal or organizational relationship with the P.L.O.

Any links with the P.L.O., no matter how limited, would give legitimacy.

Any links, no matter how limited, would tacitly approve the `rule of the gun’

and tacit approval to the rule of the gun.

Dr. King, in his letter from the Birmingham jail, included a story to illustrate the rewards of perseverance in the nonviolent tradition. He wrote about 72-year-old black woman who walked a long distance every day during bus boycott. Frequently she was jeered by hostile whites; she was tired and physically weak, but she refused to use the buses. Someone asked her why she continued to support the nonviolent protest. Her response, I believe, will always be precious; “My feets is tired,” she said, “but my soul is at rest.”

By shunning and condemning the terrorism of the P.L.O., we too can be assured that our souls will be at rest, as we preserve our tradition of nonviolence.

Bayard Rustin is president of the A. Philip Randolph Institute, an educational, civil rights and labor organization.