Beckett Failed Better, Pryor Went Electric (pt 1)

Samuel Beckett and Richard Pryor: How their tragicomedy Saves and Enlightens us.

Samuel Beckett (photo by Gyula Halasz) & Richard Pryor (photo by Marianna Diamos)

by Dennis-Leroy Kangalee

Samuel Beckett. Richard Pryor.

Richard Pryor. Samuel Beckett.

Pryor. Beckett.

Beckett. Pryor.

“All of old. Nothing else ever. Ever tried. Ever failed. No matter. Try again. Fail again. Fail better.”

This quote from Beckett’s ultimate novella Worstward Ho (1983) is one that could apply to Richard Pryor’s literal life. One, had he been a tattooed inmate of this universe - which he plumbed through like a torpedo - that would have been scrawled on his arm. It not only could be a striving addict’s mantra or a rebel’s reminder, but an affirmation for all of us who leap and try but always find ourselves disappointed either in ourselves or the world around us. It is the artist’s Hail Mary.

Warning: There are numerous expletives in some of the links to the works that are shared below. Viewer/listener discretion is advised.

Sadly, it will seem strange to some to equate these two geniuses in the same sentence but ignorance is not something we can concern ourselves with here. Because all affirming geniuses are reflected in each other, the way two very talented people might attract another. I don’t think Beckett or Pryor would object to these equations - for both, despite their draconian singularity, were two artists deeply devoted to communing with their imagination and their audience. And they both bewitched us. Understanding most of what gets under our skin, but really insisting that we get under theirs – in order to understand a little about what goes on when the lights are out. Not because someone turned them off but because their characters may never have had lights on to begin with. They were lights unto themselves, illuminating whatever darkness they could.

Samuel Beckett and Richard Pryor wrote of hunger, poverty, drugs or alcoholism, sex, loneliness, regret, death, injustice, survival and so much more.

They looked for a god and were consistently disappointed.

They ultimately concerned themselves with the operas of the tramps and the marginalized. Some would even call them the losers of our society. But not these guys. No. Losing, winning - these rarely appear in their lexicon; their heroes were simply trying to retain a semblance of power over their existence, maintain a grip on their life in a world they knew was upside down and senseless. Rationale is not what you read Samuel Beckett’s words or listen to Richard Pryor’s recordings for. It’s to witness someone else strive to find meaning or discover sense of their own identity. And then to experience the tragedy or comedy within them. It’s the biblical weight of their insights, their wit, and their devastating intelligence in the face of all the Goliath’s surrounding seeking to crush them.

Both artists shared an absurd vision of life and knew the game was rigged: they weren’t stupid, didn’t suffer fools and were simply looking for the best way to play this chess game of life, this battlefield of madness.

At the end of Beckett’s most famous play Waiting for Godot (1949) his two homeless wanderers, Vladmir and Estragon, resign themselves to doing nothing at all, after waiting for nothing and no one to actually save them. A better tomorrow? A better future? Will it come? After learning that a man named Godot will soon arrive to help them (possibly the next day?), and ruminating on suicide and adjusting a belt for pants that are too large, they decide they’ll leave but remain in the same mysterious, deserted place the play began, waiting…yet agreeing they should go. Go where?

Estragon: What’s wrong with you?

Vladimir: Nothing.

Estragon: I’m going.

Vladimir: So am I….

Estragon: Where shall we go?

Vladimir: Not far.

Anyone who knows the play and Richard Pryor’s work could easily see Pryor acting that scene out in one of his routines. Similarly, you could see Beckett writing one of Pryor's resignations and exasperated truths - like the line about having to go before a judge to get “justice”. So he goes and what does he find?

“Just-us.”

Meaning Black people. The oppressed. The forgotten. And so on…all constantly looking for something they will never get. The image is extraordinary. His word-play is so deceptively simple that it becomes a revelation.

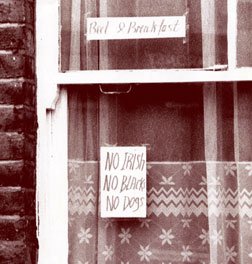

These truths, through drama or stand-up comedy, are carved down to a severe sense of actual life emboldened by the author’s taste for the macabre and black comedy. They were masters of two different kinds of theater, but all part of the human comedy. Philosophers of a Kafkaesque world where authority and law were insidious (not to mention inept) and life itself was often something always to be slightly offended by.

*

Waiting for Godot was so ahead of its time it was a disaster when it first premiered in America (starring Burt Lahr, famous for playing the Lion in Wizard of Oz, who admittedly didn’t quite understand Beckett’s play, but the precocious director Alan Schneider knew he had entered a whole new realm when he saw it originally in France and he was compelled to stage it. In Florida. Where the audience actually hissed before absconding.) Beckett’s philosophical vaudeville is the most famous play of the twentieth century and the most debated. Like Picasso’s Les Demoiselles d’Avignon (Young Ladies of Avignon) in 1907 it helped to rewrite all the rules and preconceptions about what art could be and what content meant. It discarded the psychological realism of Stanislavski and destroyed all semblance of subtext or meaning; its characters in despair were front and center, with philosophical discussions, diversions, no explainable plot in sight or intention. The absurd vision of life was born. Beckett went on to write greater or more challenging plays (Endgame, Happy Days) but certainly I discovered, after working on it for so long myself, that his most accessible play is his 1958 masterwork, Krapp’s Last Tape. A monologue.

This is relevant because like all great dramatists Beckett was a master of tension and his dialogue is among the best ever written. But he actually wrote more and more monologues as he got older, and his finest accomplishments post 1970 are the astounding solo plays for women: Not I and Rockaby. (The combined running time for both of them is about 24 minutes)

Read them and ask yourself “Who else could understand this but a stand-up comedian?”

Richard Pryor and Gene Wilder: You could have imagined them together as Estragon & Vladimir in Waiting For Godot (1989, promotional still for See No Evil, Hear No Evil)

Both Beckett and Pryor’s genius resides in their overwhelming linguistic agility and understanding of words, (and in Pryor’s case - physical prowess as a performer, which too few comedians today even attempt, nonetheless possess) their uncompromising imaginations, their desire to express the inexpressible, and their mysterious relationship to the twitches of their souls and its transference to an audience.

Pryor and Beckett break down barriers, walls. Beckett’s cerebral public persona and aloofness may have alienated mass audiences making him the ultimate “cool” cult icon, but his coterie of admirers are as passionate and emotional as Pryor’s. Similarly, while Pryor’s “hot” persona as the wild-man-child who leaps before he thinks, following every Dionysiac impulse in the world that leads to sex and drugs, pushing Apollo to the side – is a bit erroneous. It’s simply not true. His voracious obsession with stimulants, new experiences and the sensual have been long mined by Romantics, from Rimbaud to Marvin Gaye. There is a very grave and sober side to Pryor's recklessness. His questionable behavior at times, could be perceived as a personal test or spiritual battles he had to engage in – in order to be free.

This is not to romanticize Pryor’s addictions, abuse, or downright despicable behavior at times. It’s to grant it a bit more context.

Beckett was nowhere near as tortured and therefore as self-destructive as Pryor, but he also was not a literal political prisoner. The stormtroopers against him were more abstract, less literal. The Ku Klux Klan in his world would be out to castrate his imagination solely, not brutalize him for who he literally was. And he had fled Ireland well before the violent revolutions against the British colonialists. But, understanding the odds against him as a thinker and artist, he too was searching and pushing in his art. That’s one of the defining features of any extraordinary artist as well. Racial, religious, sexual or gender persecution aside, any artist in any time will always be at odds with his society. While both artists were not quite socially comfortable, they could both slay and put to rest what they needed to. Beckett had chess. Pryor had drugs. It sounds flippant, but it’s all a means to an end. The problem is when the route you are taking doesn’t work or help you to become a more stable, more secure person.

Richard Pryor gave a whole new vision of art so intensely and so completely he accomplished - just in American pop culture alone - what Bob Dylan did overall: punch a hole into the universe and make everyone else see through it. And like Dylan, he went a step further by “going electric.” In 1979, he transitioned into his this next revolutionary phase when he visited Nairobi and threw down the gauntlet in December 1981 when he challenged his audiences to grow and move on from the word they were shackled to in all its forms: “Nigger”. And up until his very last performance film he seemed to be conscientious of pushing love to the center of the floor. Love yourself, Black people! It was his literal “Say it Loud, I’m Black and I’m Proud!” moment. It was completely on bar with James Brown’s anthem and it was affirming. Pryor had taken “nigger” as far as he could and, unfortunately, had to concede that not only is it not our word – it can no longer do what he did with it - a decade earlier. Which was liberate. Hilton Als, writing for the New Yorker, in a phenomenal display of unconsciousness and conformity, criticized Pryor for this change, in what is in an otherwise dignified piece of journalism. Als foolishly believes that Pryor was somehow bending to the 1980’s Republican tide in the Empire Strikes Back era. Als’ transgression is unforgivable. Pryor even received death threats when he courageously abandoned the word “nigger” and declared he was growing as an artist. The same way the folkies decried Bob Dylan a Judas when he performed “Maggie’s Farm” in 1965 with an electric band.

Love is something that Beckett and Pryor want and struggle to attain. Few, if any, of Beckett’s characters discuss it and yet it is always there…in the text, in the drama, in the meanings between the words and the page.

Where Pryor was able to be vulnerable to audiences, his sentiment was never false. This is very akin to Beckett’s disdain for false emotions and their shared hostility towards hypocrisy.

Beckett couldn’t stand seeing animals in harm anymore than he could human beings. Pryor was similar. In his 1983 Here and Now concert movie, performed in New Orleans, Pryor’s sensitivity shines as he rescues some kind of crustacean in the opening (it’s in his water!) and grants the audience a final monologue from his most beloved character, Mudbone the old man from the old South who sounds like a Zora Neale Hurston character coming out of the back of a bar in Detroit or a Harlem barbershop, who always preached love. (Pryor’s rural, small town Midwestern sensibilities always come off as urbane and sophisticated. Like Beckett, who was not from metropolitan Dublin, but from a suburb called Foxrock. They both set a standard, however, for the coastal, urbane circles years later.)

This is a man who laughed at his own suicide attempt and made divine art out of it eighteen months later. He never shied away from his disasters, his foibles, his naked truths, his miraculous failures. And most importantly what he discovered about himself. He shared his findings, like a brave explorer. On June 8, 1980 he attempted to end his life by dousing himself with rum and flicking a lighter. In that instant he became an Artaudian* figure – “an actor burnt at the stake signaling through the flames.” In his legendary Live on the Sunset Strip released in 1982, he delivers one of the most memorable monologues about the ordeal from the night he immolated himself to his eventual recovery in the hospital. The entire routine is a Beckettian play. I mean, the man ran down the street. On fire. Everyone from Buddhist monks to activists to psychedelic poets would relish the image. But also, everyday Irish bar keepers and Black nurses. Those who’d seen and felt it all – inside. The pain and the comedy of life.

The late great Paul Mooney, Pryor’s collaborator and co-writer, always said, as you will never have another Janis Joplin, Jimi Hendrix - you will never have another Richard Pryor. For he, like Beckett, “examines the most basic foundations of our lives with strikingly dark humor,” as the Nobel Prize organization stated when granting the award to Beckett in 1969.

*

Art should bind us. Not divide us. Celebrate our differences, acknowledge our similarities, destroy what oppresses us. Too much modern day art is built on the cliché differences and stereotypes of different groups and races. That is a reactionary art, not a progressive one.

socialist playwrights and radical humanists: white Irish Sean O’Casey and Black American Lorraine Hansberry

Charlie Parker and James Joyce: 20th Century titans who ushered in new perceptions, paving the way for a Beckett and a Pryor years later.

*Photograph of Charlie “Bird” Parker: William Gottlieb/Redferns

The cultural, political and artistic connections between the people of Ireland and Blacks of America are substantial and extraordinary. Interesting side note: James Joyce and Charlie Parker both had what they felt were “epiphanies” around the same time 1939 when Finnegans Wake was published and Bebop was born. Lorraine Hansberry once remarked to Studs Terkel that the Irish family as written by the playwright Sean O’Casey was similar to the Black-American family and she drew inspiration and conscientious parallels in hers and his plays.

*

ON MONOLOGUES - COMICS and BECKETT

Beckett’s Happy Days (1961) is a play centered around one of the most powerful images of modern theater: a woman dwindling in sand, in a deteriorating earth – but remaining delusionally optimistic. That’s a brilliant sledgehammer about the condition of women in a patriarchal society, the brutality against mother nature; it’s a presentation of our life’s condition in a world that wants to swallow us up whole. Equally funny, sad, and strange.

The estrangement of voice, body and soul: Richard Pryor, in an early television appearance - possibly Ed Sullivan - was a master of physical expression in addition to his aural acumen. Billie Whitelaw (here in her rendition of “Happy Days”) is one of Beckett’s greatest interpreters. She had an incredible perception and ability to express feelings and ideas without getting bogged down in cerebral, intellectual answers of “what does it mean?” The comedy and tragedy of life is understood, felt and rendered. It cannot function as art if you are looking for straight answers.

What Shakespeare does in four pages, Beckett does in four lines. What a film director or classical conductor does with an army of performers, Pryor does with his one body. He makes his body ‘sing the electric’, he distills, focuses and inhabits. And through his own incredible jazz-like transitions and almost surreal images of life that spin out of his mouth — he reaches further, wider, and deeper in 50 minutes, 90 minutes than anyone could in ten movies. New Yorker critic Pauline Kael declared his touchstone 1979 Live in Concert movie (footage of his September 1978 concert that resulted in the smash album Wanted) “the greatest of all recorded performance films”. Beckett’s solo plays are exquisite texts for actors who dare to do the same, as tragedians. What Richard Pryor did as a stand-up comedian exceeded everything (still does) most actors could ever attempt. In fact, observational comic David Brenner (the most frequent comedian on Johnny Carson’s The Tonight Show) claimed that Pryor’s routines were “really more like plays, one-man theater where he plays all the parts.”

Krapp’s Last Tape is a play about an old man listening to recorded diaries of himself as a young man, reconciling what he planned to be and what he is now, in an apocalyptic future. Krapp is one of Beckett’s obvious, silly play on words as his character, suffering from constipation, is a vociferous devourer of bananas! It’s a gentle and touching nod to the digestive problems of age and middle finger to the establishment. He brings the word “crap” out ONTO the stage, into the theatrical establishment and creates a whole new meaning out of it. He was probably tickled pink doing so in 1958. Similarly, in 1971, Pryor’s album – Craps (After Hours) blew the roof off his previous work and became in that instant the greatest modern comedy record, setting the tone for all the glorious profane and profound routines of Black street life, Pryor’s anarchic inclinations and his marvelously surrealist sensibilities.

A person can choose their Krapp/Crap and their meanings:

Inmate turned artist, Artist turned outlaw: Photo: Rick Cluchey (left), courtesy of NY Times; Dennis Leroy Kangalee (right) by Edwin Pagan

Rick Cluchey, of the San Quentin Drama Workshop, in Krapp’s Last Tape in 2013. Cluchey was an intimate collaborator of Beckett’s. He died in 2016. The 1958 play was originally written for the great Irish actor Patrick Magee who was the first to perform it. The author of this article’s own interpretation which was workshopped for a year, combined Beckett’s Irish gallows humor with a Black “punk rock” West Indian sensibility, and culminated in a limited engagement for the public at Studio 111 in Brooklyn in November 2022. Although it was another comedian that spirited the approach to this rendition (Redd Foxx in fact!), I came to the realization that Beckett and Pryor were linked somehow after almost a year of rehearsing the play.

The poster (left) for my recent 2022 production of “Krapp’s Last Tape” , which led to the birth of this essay & sleeve for Pryor’s own “Craps” his landmark sophomore album. 1971 was the first transitional period for Pryor - from relatively tame, yet funny, material into more socially conscious and provocative sketches.