Re-Assessing Gordon Parks’ Legacy and Mainstream Black Image Makers Of The 1970s

by Dennis Leroy Kangalee

"I don't make black exploitation films," Parks stated to The Village Voice, the very year I was born, in 1976.

Gordon Parks, Self Portrait [circa 1950]

After working at Vogue magazine, a 1948 photographic essay on a young Harlem gang leader won Parks a staff job as a photographer and writer with Life magazine. For twenty years Parks produced photographs on subjects including fashion, sports, Broadway, poverty, and racial segregation, as well as portraits of activists, artists, and athletes. He became "one of the most provocative and celebrated photojournalists in the United States." (Lee D. Baker, 1992, Transforming Anthropology)

***

Astoundingly, one of the most underrated and rarely referenced filmmakers is Gordon Parks - whose genius as a visual artist and photographer often hijacks the attention away from his dramatic works and his cinematic expeditions. His powerful photo-essays, his dignified pictures of urban and rural working class life, his career as a Life magazine photographer (the very first African-American on their staff!) alone has left an indelible mark on the 20th century and modern culture alone (find his haunting "Crisis in Latin America"/Poverty/Flavio series, "American Gothic," or some of the Harlem photographs he took, or his iconic depiction of Ingrid Bergman in Italy, peering back out of the corner of her eye as three villagers admonish the affair she was having with Roberto Rossellini)

Capturing the moment: Ingrid Bergman on the Italian island of Stromboli (Gordon Parks)

Gordon Parks is on my mind today because I could not help but think what he would have done with the Western genre. Jay-Z and Netflix’s corporate The Harder They Fall directed by Jeymes Samuel ignited this thought. I kept thinking that the Western might have been something Parks could have really delved into, from a personal place. Kansas. Horses. Slow moving cowboys heading homeward after a long day...Parks is one of the few filmmakers I am intrigued by due less to his personal life or work than by the image projected by the media. Years ago I overheard some moron in the Time Life Building (which hosted Parks’ haunting portrait of Ingrid Bergman) ignorantly yelp that he was the "Father of Blaxploitation cinema." In my younger, meaner "old days" I'd have started to yell and promptly given it to this kid straight between the eyes.

I delicately explained to this young man that Black filmmakers did not create "Blaxploitation" cinema and if they did they certainly would have come up with a better term.

I had to explain that because of the box-office success of Melvin Van Peebles powerful Sweet Sweetback's Badasss Song and Gordon Parks own cop thriller Shaft, white Hollywood executives and producers took note of this, saw dollar signs, and instantly jumped on the "craze" that was emanating out of Black consciousness, music, literature, and theater in the early 70's - spilling over into film. It was imminent that Hollywood would be influenced.

Black Panther San Francisco Chapter Headquarters, 1969 (Gordon Parks)

But instead of truly honoring the intentions of such grave filmmakers and writers (Sam Greenlee, Ivan Dixon, Bill Gunn, etc) -- many of these filmmakers were lucky if they made one personal film of their own that ever saw the light of day. And even when merely "hired" they rarely resorted to exploitation or sided with the racism of the establishment by further peddling stereotypes and all kinds of bizarre images of African Americans that the seventies mainstream began to feverishly churn out (as if it were a return to the sickening images and propaganda published about Blacks during the height of chattel slavery). Those that did had to deal with their own conscience, if not the reprisal from another Black artist.

Not one worthwhile Black artist benefited from Hollywood's exploitation of "Black anger", fashion, sexuality, or music. Instead white producers wrote garbage and "pimped" Black men and women into portraying white fantasies and racist caricatures; often watering down the righteousness of the previous 1960's visceral rage.

And often - we allowed this to happen.

Some directors, like Michael Schultz, found ways to transcend Hollywood's attempts at gross exploitation of the African-American audience and community at large. Check out his heartfelt, coming of age story Cooley High, and his hilarious Car Wash -- two films that bridge a universal satire with social commentary. Incidentally, Roger Ebert praised Car Wash, comparing it to M*A*S*H. But despite the film having received a Golden Globe nomination and a nomination for Cannes’ 1977 Golden Palm, it somehow became considered a "bad" movie in the USA with mediocre reviews. What's even stranger about the screenplay for Car Wash is that it is credited to Joel Schumacher (yes, the man who directed St. Elmo's Fire and the mid-1990's BATMAN movies. Don't ask.) I have heard from at least four people that Schumacher simply plotted out the movie and all dialogue was improvised and rehearsed and honed by Schultz. (Schultz is a theater director and so this would not have been alarming for him to do as he came from a heavy ensemble and actor-oriented background. Look him up: he directed Waiting for Godot in 1966 at Princeton and directed for the Negro Ensemble Company. He is noted for having directed Lorraine Hansberry's To Be Young Gifted & Black, the most successful Off-Broadway play in 1968!)

Interesting to note, like one of our greatest playwrights - August Wilson - Schultz, too, was Black and German. I sometimes even wonder if this does not account for their conscientious and laborious way of working; taking two great work-ethic traditions and blending them into one to singularly express a unique POV and varied experiences of the African-American community. That’s what I expect from high-brow academic "cinema" magazines and essays to be writing. Not promoting salacious and atrocious lies depicting Gordon Parks as the "Father" of Blaxploitation Cinema, making him "easy" and "pat" for movie academics and white kids in the suburbs. IMDB is so disrespectful and perverse – they attribute Parks’ Shaft to Blaxploitation while even acknowledging the quote that starts this very essay!

Women, Nation of Islam, Harlem 1963 (Gordon Parks)

Back to Gordon: Kurt Vonnegut, Jr. once praised him as being a "Black genius," - he iterated Park's race because the interviewer obviously had no clue who he was (can you imagine?)...For those of you who don't know much about Parks either - treat yourself to one of his autobiographies "Fires in the Mirror" or "A Choice of Weapons", borrow a book of his photos from the library, or at least watch the documentary on him Half Past Autumn (produced by Denzel Washington, in fact one of Denzel's more sincere contributions to cinema).

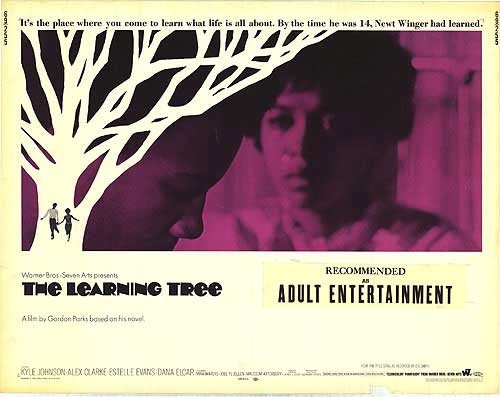

"Gordon Parks was the first black director to make a major studio film, and his 'The Learning Tree' was a deeply felt, lyrically beautiful film that was, maybe, just too simple and honest to be commercial."

- Roger Ebert

The Learning Tree poster (1969) Interesting that it states “Adult Entertainment.” This must imply that most things “Black” and “movie” were juvenile, no?

Parks' films seem boring today to a lot of the film establishment and are unnoticed or shoved aside by the independents because they are not formally aggressive and - aside from the 'sexy' Shaft and his gun-cop-adventure movies - are rather slow moving. His personal movies are not loud or stylistically excessive - they capture moments, like his photographs. You can feel his colors, his environments. They are distinguished - as he was - and they reek of cigar smoke and well-kept sweaters. And they build and have a slow, gentle impact. They are not provocative, but they resonate. They are not fast and extravagant, but they are deep and conscientious. The Learning Tree of course is a perfect example - powerful due to its lean and delicate nature and how it depicts more complicated aspects of racism and reveals that everything is not what it seems. And yet...regarded as a strange anomaly. At the height of the civil rights revolution, the movie seemed tame even then and in a certain sense was, understandably, disregarded by the more politically radical Black arts community that were re-establishing and re-assessing how best to move on and create in America. Some believe it is because Parks was telling a story set in the 1920's and the accepted racism of that era did not strike a chord with the revolutionaries and the activists of the time who, in 1969, wanted nothing to do with any memory of the 1920's...they wanted to destroy all that had abused and humiliated the preceding generation and their very own. The Learning Tree, although well done, seemed "conservative" and passé at the end of the tumultuous Sixties.

The Learning Tree supposedly had little impact upon later African-American artists and is seldom discussed as a significant work of art, despite Congress' inclusion of it in their national registry as an "American treasure."

Parks' Leadbelly is an excellent 'biopic' (and I hate biopics) and a film that meanders somewhat tracing the life of this Blues legend in a confident and understated way. Parks was a director who used understatement and slow-pacing in his own way, sometimes his films feel like they are trying to find themselves as it were -- but while Schultz was definitely a better craftsman, Parks was a better artist.

Even his minor works reveal something about the painful side of life. Solomon Northup's Odyssey, his version of 12 Years a Slave, is under-cooked, but better than the overrated Steve McQueen version. But of course no one will mention this. Parks made his version for American Playhouse in 1984 with Avery Brooks. His version has more gravity and heart than McQueen's. And yet he doesn't push for it...McQueen pushed heavily on well-worn buttons and insipid cliches. There was a disturbing laissez faire quality the movie had and all I was left with was Chiwetel Ejiofor’s beautifully weeping eyes - with nothing behind them. At all. Those eyes should have given Rene Falconetti's (see Carl Dreyer's Passion of Joan of Arc!) a run for her money and they didn't. And that's why ultimately I was angry at McQueen: he pushed and choreographed so much melodrama - that all we were left with were soap suds.

Did you know that it was the original movie maverick himself, John Cassavetes, who demanded that Warner Brothers give Parks money to make an adaption of his own book, "The Learning Tree" into a movie? Parks recounts this in his autobiography. And the legend goes that Cassavetes basically just told the studios that Parks’ book was the best thing out there (even though he hadn’t read it) and that if they didn’t let Parks make a film out of it and there would be serious consequences. Perhaps in the midst of Black revolution in the streets, the Hollywood henchmen got nervous? Who knows? It’s funny thinking about it because one could imagine Cassavetes calling Parks up, laughing. I'm always amazed when biographers of John Cassavetes never bring it up: it took a lot of guts to go to bat for an "unknown" Black director in Hollywood in 1968! This warrants serious rumination. Who would do this today?

Mavericks: Cassavetes & Parks

Filmmakers are a selfish bunch. A part of us has to be because we're always nervous about financing our work, we often get derailed trying to organize our projects, we're very competitive with other filmmakers (a good thing), etc. – but we seldom go to bat for other filmmakers. And understand that Cassavetes was no Richard Burton or Marlon Brando, mind you - he never had that Hollywood power. Ever. And so he had a lot to lose - but by 1968 he already had a reputation for being argumentative, righteous, intense, and "artistic” as a director. This was a filmmaker who wrote and directed his own dramas in his own home, using his closest friends, and shooting films like a jazz musician. Pure, unfettered feelings and emotions and thoughts - barely with a "story." It takes genius to recognize genius and this example proves it. If there were two mavericks in Hollywood or American cinema at that very moment, it would be Parks and Cassavetes. Parks did not have the flair or showmanship that Van Peebles had and Cassavetes did not conform to genre or give audiences what they wanted the way some of his smarter contemporaries might have (Altman, for example) but they both created a very personal body of work. And a very important one. And that is how one ultimately should assess the worth of filmmakers: how personal is it?

1963 (Gordon Parks)

A final interesting fact: Did you know that the great Gordon Parks -- the pipe smoking, distinguished man of letters, music, civil rights, film, photography -- was also, in addition to having dolled around with Gloria Vanderbilt, Candace Bushnell's boyfriend when she had fled Texas to live in NYC? He was 58. She was 18. According to Bushnell, she was too young to be in a real serious relationship with a genius, but declared Parks was "great" and that her mother thought Parks was the most charming man she'd ever met. Bushnell would, of course, go on to write and create Sex and The City. The only thing that disturbs me about all this is that Carrie Bradshaw always seemed too awkward and self-consciously nervous to be around a man like Gordon Parks. It bothers me that Bushnell never tried to truthfully render a relationship between her characters and a Black man like Parks. That would have been edgy. But her experience with Parks and Studio 54 was in the 1970’s. Her Sex & the City is like the 1970’s without the radicalism, intellectualism, politics, or danger. The 1990’s in NYC was interesting, yes – but if you remembered the show Sex and the City then you probably weren’t living it. And if you were – it wasn’t necessarily devoid of radical politics. When those incongruous worlds meet, it certainly makes for great drama. I’m mystified why it scares so many people.

Anyway, there you have it. Don't ever say I didn't give you any interesting gossip!

Lastly, please remember: it is this charming, elegant man -- this high school dropout -- named Gordon Parks, who lived life on his own terms, and tried hard to create a rich and varied artwork that would resonate with people who took just a little time to care and who were craving aspects of their own reflections...or society's illness.

His films warrant closer readings and "remastered" viewing.

Gordon Parks on the set of his hit film "Shaft" (1970)

All of the pictures used in this blog entry and all WAVELENGHTS entries are used for educational and illuminative purposes only. We do not own the rights to any of these pictures.