Jeffrey Wright: The Invisible Man (part two)

the indomitable Jeffrey Wright in Ang Lee’s RIDE WITH THE DEVIL

by Dennis Leroy Kangalee

While his bank account is acknowledged his extraordinary talents aren’t. I know that is a provocative declaration - and that is not a criticism of anyone except the establishment. Jeffrey Wright has done so well financially as an “artistic actor,” it is as if he is remunerated to not act. In other words, I feel Wright is being paid to be looked at, but not seen. But my entire Invisible Man simile breaks down, really, because Wright is less an invisible man than he is gagged man. If he’s hired to play trumpet, they prefer he has it muted. Anyone reading this who has ever excelled, innately, at anything in a social context will immediately understand what I am saying. And perhaps it’s for you that I write this…

Wright’s ability as an actor is so robust and startling, an industry built on corporate entertainment, gangster enterprise, and historically racist tropes can’t help but find a way to tame an “entertainer” like this; paying them to NOT act as it were, and to exist front and center while remaining marginal. It is a damnation and a curious conundrum because only the very conscientious notice this and especially the conscious Black artist or entertainer who can see right through it.

The curious case of Jeffrey Wright will never cease to confound me and I dislike the pretense surrounding the conversation amongst actors, especially, that there is no problem here. Wright’s charisma, on screen alone, endowed him with an energy that he should have been able to take in different directions, with like-minded auteurs. Where many actors on his professional level willfully phone it in, Wright is almost forced to commit himself to using his talents even as they are somehow

hijacked, pushed back, held in check or remarkably whitewashed…(the James Bond flicks, Batman, etc)

The delicate complexity and nuance of his acting is often destroyed, undone, or disabled in the editing or the director’s vision itself. And if there is a vision for how to use Wright, those visions are insulting, if not demeaning. Watch him in Goldfinch, in Broken Flowers - the performances, although different characters, almost translate to the screen in the very same way. All successful film performances are the result of the director/editor and actor: a holy trinity that is as much confounding as it is practical and obvious. Bette Davis, who brought the dynamism of live performance to the screen, disturbed Hollywood directors and producers with her emphatic style of acting. The studios knew she was talented, they just didn’t know how to use her. An awful fate would have befallen Davis or a James Cagney if there were no directors who were empathetic to their personal styles. Orson Welles, himself a victim of this unless he was directing his own films or acting for Carol Reed, on more than one occasion has tried to explain the mystery of how some actors can transcend an audience on stage but be powerless onscreen. Often this is not their fault: for whom the camera falls in love with sometimes is a riddle itself even to the most capable cinematographers.

The crime here is when an actor has been rendered powerless on purpose by the filmmakers; it is a crime no less appalling than sterilizing the marginalized humans in our society and leaving them to flounder in a corner of a room.

It’s odd that Jarmusch (a director who you would think would cherish Wright’s offbeat abilities) doesn’t know how to present him. He slaps Wright onto his canvas in nearly the same way John Crowley and Amazon Studios the director and producers of Goldfinch, respectively did. The only parallel I see between them is that they are all white. Is that really the reason why this bizarre and even unconscious conspiracy is taking place?

Jeffrey Wright is the ONLY internationally renowned actor I know of who acted twice on stage in New York, in different plays, with the grossly underrated Ron Leibman and didn’t end up being chewed to tatters. Liebman, like Al Pacino, represented the last of the old New York declamatory, aggressive acting style. Urgent and passionate, it’s a mix of Shakespearean zeal and Big Apple ethnic neurosis. One reason this mode of acting no longer exists is because the global village of the internet and the gentrification of the world has homogenized humans in a way never seen before. Westerners, in particular, are more and more like each other, their only claim to singularity is their membership cards: to which identity politics game they belong to or want to play. The Jews have abandoned their moxie and recognition of their history of oppression in Europe - something they tried, at least, to apply and use to create empathetic alliances with Black Americans fighting against their oppression in North America. The anger, resentment and gallows humor of white ethnic tribes like the Irish, Italians too – have disintegrated into bizarre stereotypes or have simply rendered them even more boring and uninteresting as the supposed WASPs were deemed to have once been.

African-Americans have forsaken genuine anger for a milquetoast bastardizing of our insightful edgy social consciousness and we have willfully given up our remarkable energy and style for any sort of mainstream appeal, commercialism, or acknowledgment by the establishment. And we do it now demeaning our ancestors or Black radicals who fought for us. Nowadays, all Blacks are “activists” the same way all women are supposedly “feminists.” When this happens, the system had rendered you hollow and so it is easy to control you. You can see all of this has

impacted the theater: Broadway and regional theaters in America simply want to be live versions of bad movies. How is that possible?

Theater is less urgent, its actors less dire, its language less and less drastic. Streaming and limited series aping the British masters of understatement or well executed anxiety on camera - without exploding - or demonstratively feeling – have been the new Acting for Screen Master Teachers. To its detriment, theater has followed suit. Jeff Bezos, The Koch Brothers, and Netflix have more impact now on acting than Lee Strasberg ever did. You notice even more when you look at American actors in period pieces. Somehow, their faces, even body language doesn’t seem to work. It’s apparent, too, in all the cop shows. There is a pat, easy, safe way to behave in front of the camera, that is perfunctory.

If Jeffrey Wright had more allies in the establishment he wouldn’t be giving interesting performances in white films that push him to the side.

If Generation Z could watch Andre Braugher in the 1990’s Homicide TV series they’d have an understanding as to what acting above and beyond could actually mean (and how you could, ironically, play a policeman…with a soul.) And that “big” acting does not denote broad, hammy acting. It is direct and focused, like a knife as Orson Welles once said, in full support of this type of “playing to the stadium” acting like the grand performances of James Cagney. If Blacks had soul music, at one time even Hollywood had actors who were both vulnerable and courageous enough to give their all on screen, never worrying if they were “too much” or “too big.” The different mediums and forms aside, one cannot imagine James Brown “toning it down” for anyone.

Of course, this prompts one to think about what is acting and what does it mean to them? Well, what does music mean to you? And have you seen as many forms or collaborations in acting/film that are as comparable? I maintain that if Wright were a musician, he’d have legions of artists, many Black, from different backgrounds, who’d want to let loose and explore with him. Since the professional actor (as trade, not art) is a creation of the entertainment business, we immediately can see how hemmed in they can be. Especially if they are “dangerous” like Jeffrey Wright. In that prism, however, actors are extremely well paid hired hands. Some are just well paid slaves to the entertainment industry as there are million dollar slaves in the world of professional sports. Let’s just call it what it is. They don’t have as much autonomy and control as one might think, which breaks down into a whole other labor, ideological, and artistic conversation. What’s telling is that despite being a professional working actor for nearly four decades, Wright is still at the mercy of “big brother.” The commercial world has nothing to do with art or cultivating ideas or healing society. It’s an industry like any other. But the type of treatment that a “big, well paid actor in good standing” like Jeffrey Wright gets - is a bit too much to swallow. Look at this May 23, 2023 interview excerpt from Deadline magazine below:

DEADLINE: This interview is going in Deadline’s Cannes magazine. What’s your experience with Cannes?

WRIGHT: I’ve never been! This will be my first trip. I’ve had several films there, and, for one reason or another, I didn’t make it. Mostly because I was working, and they wouldn’t let me. For example, the last time Wes had a film there, I was fully planning to go, and then I believe it was Westworld that didn’t see fit to allow me to take time off to go.

The producers of Westworld didn’t see fit…to allow Mr. Jeffrey Wright to go to Cannes? What does that tell you, dear reader? (Don’t be angry at me folks, I’m just planting seeds. If they sprout, more power to us. But damn.)

No, Jeffrey Wright is not invisible at all. He’s quite conspicuous. This is why the cobweb he’s in is so disconcerting.

Let’s be clear: this is not an assault on employment, craftsmen, what one does for money (all money is corrupt, I could care less). This is about the show business industrial complex’s conscious attempt to hem certain actors in, to keep them almost at odds with the actual reasons the world responds so passionately to Wright’s talent.

Jeffrey Wright, the artist— with a handful of others - and they are rare - deserves better. I do not critique the establishment, nor the show business core that maintains and promotes a very bizarre star system and criterion for its “A List” — I am concerned with what Black patrons, fans, admirers, cultural workers, artists, (of all ideologies) even businessmen who claim they have a cultural and political investment in the utilization of cinema, will do to celebrate and enable the rare talents like Jeffrey Wright.

It’s a problem for actors who are artists, but unable to write and direct for themselves. The first thing a seriously intrepid, and innately intelligent director would do, would be to write a script for Jeffrey Wright, Giancarlo Esposito, Guenveur-Smith to act in. That alone would be a tremendous start. And an incredible way to shed light on a multitude of talent, skill, and energy as we have not seen in a long time. For all of my criticisms of Spike Lee, at least Lee had a sharp eye for Black actors’ talents when he made his first five films. He was aware not only of the gradations of skin color, different faces, but also the varied energies and personalities that make up an ensemble. It’s a pity Spike Lee’s

ambition was simply to be part of the academy and prove that middle class Blacks just want to be as bourgeois as anyone else. His anger, although not genuine outrage, was fun and invigorating in cinema when he was in his early thirties. But it had no weight. Lee was just angry he was not given the opportunities or budgets white directors were. And while his politics are actually quite middle of the road, he lost his knack early on to shape scenes and cultivate character. I couldn’t imagine a Jeffrey Wright-Spike Lee collaboration any more than I could Paul Thomas Anderson directing Forest Whitaker. And I don’t say this proudly.

Anyone who reads me knows my concern for the actor-director relationship if dramatic motion pictures are to have a real future. And to be honest, if Anderson could make the extraordinary There Will be Blood (quite possibly the best parable of Anglo-American capitalism outside the misunderstood Godfather or Cassavetes chilling Killing of a Chinese Bookie) and the interesting, but flat, Phantom Thread with Daniel Day-Lewis then anything is possible.

It’s not a casting director’s job to ensure that Jeffrey Wright’s talent is used nor is it his agent’s if we are honest. Wright is a rarity that does not take on degrading or roles that serve the magnitude of American nationalism and he doesn’t waste your time in mainstream epics that ensures liberals can feel good for feeling bad. Yet, there are problems – his involvement in Westworld is particularly troubling only because the series, I feel, actually enables white patriarchal racism –not consciously, I am convinced the creators, as well as Michael Crichton’s initial concept – feels it’s critiquing our society rather than being part of it, but that is a trap a lot of Neo-Liberal corporate productions fall prey to. Since it is “cool to care” in our society now and since everyone and everything is political and “woke”

– everything Hollywood churns out is under the cloak of a kind of “compassionate Capitalist” mentality. TV series and most mainstream movies are checklists of identity politics, MEtoo politics or patronizing BLM sentiments - which means they’re hollow. They will concede that Big Business is “bad,” the little person is being crushed, politicians are all corrupt…and we are destroying the planet. But instead of actually indulging us with characters who are rebelling, they rather show you characters who are often quite powerful but are “corrupt.” You don’t have to be Sigmund Freud to know whom they want you to identify with. Westworld has so much violence in between its hushed intimate acting scenes with Anthony Hopkins and Jeffrey Wright, that one has to constantly lower the volume about every three minutes.

Wright is probably the only actor besides Jeff Goldblum who has a unique command over the sly, cerebral, mathematical man - with one foot locked up in his mind, the other trying to find the ground. Goldblum and Wright are, like Scully in “The X Files”, the classic Crichton personas: they are as invested in the boundaries of the imagination as they are in science and they plumb so fully…they are at risk of losing an emotional part of themselves. Although less nervy and insistent than Goldblum’s scientist personas, Wright is as believable and even more penetrating. His eyes that peer out from over his glasses, how he cradles his head – there is something infinite about it. And that’s before he even speaks. (I remember seeing Demme’s Manchurian Candidate - solely for Wright - and was impressed how Demme introduced Wright on screen: on the left side of the screen; the imperfect framing in sync with Wright’s funky performance. Demme then cuts to these overt wide-angle close ups when Wright confronts Denzel, but what is interesting is that Wright obviously knew this and he plays with that: by never looking fully dead on in the lens as Denzel may have been instructed to do – he creates a whole other energy and is able to act this. Reminds me of Herzog’s observation on how Klaus Kinski would step into a frame and project an energy at the camera and then step out of frame the same way. As if the camera is - what I believe it usually is - an enemy.)

Demme introduces Wright in a wide shot; his head cocked in that inimitable way on the far upper left of our screen, the rest of the world on our right - turning back towards him…

Then when confronted with an imposing close-up, he never fully engages the camera – his ¾ profile is probably one of his best assets when he acts on camera in his early films. There’s a remarkable neurotic edge that you can’t help but be impressed by. His eyes absolutely never trust the camera and it not only endears us to him, ironically, it transmits a message about a feeling, a state of being, the tenuousness of clarity, health, and safety. As he got older and more comfortable this obviously changed…the problem is that the directors didn’t!

His inimitable voice opens Westworld and sets the tone for its entire universe. It’s interesting because I could not help but think how fascinating the implication is - artistically and ideologically – a Black artist is the voice…of creation. In Westworld, Wright and Anthony Hopkins play God, essentially. The trap here is that Hollywood forges an alternate mindset, a “fugazi universe”, that proposes that Black artists (the Black human) have as much, if not more, control over the masses as white powerbrokers do. We know this is not true simply because we are playing the game Monopoly. And caught up in it. (Monopoly was created by the venal Parker Bros; they appropriated the original game to focus on righteous capitalist greed instead of a socialist lesson - created by the feminist game designer Lizzie Maggie!)

In nearly all of his film roles, Jeffrey Wright’s voice is modulated, controlled, and tweaked as he sees fit. Aside from his latent physical approach to acting, is the wonderful oddity of his deep, tentative voice. He is aware of his theatricality which he utilizes strategically through his voice. Increasingly, however, Jeffrey Wright is cryptic, he acts - speaks - as if either constantly conspiring, communing, or simply running his own thoughts through his head. Wright has a penchant for bending the characters to himself, despite how artificial the behavior may seem.

The adjective “mannered” is more accurate – a term closely associated with actors like Dustin Hoffman or Meryl Streep who had a knack for straitjacketing their character’s voices or behavior. This often came out in more extreme examples or characters like Streep’s Francesca in Bridges of Madison County, an underrated performance actually, or her preposterous Margaret Thatcher; Hoffman’s Rain Man depiction is his cliché example. This conscientiousness of the tenor of his voice works well in certain movies or TV shows where Wright maintains mystery.

As Bernard Lowe in the extremely popular Westworld series, Wright’s cerebral and almost detached perception of humanity come into full view, almost the opposite side of his Basquiat, (a vulnerable sensitive “stranger”); like Jeff Goldblum he excels in those cerebral roles that require a real verisimilitude of intelligence, a kind of sensual intellectualism. It’s this that scares certain industry people. They love Wright’s intellect when applied in “white spaces.”

It’s hard to imagine Wright so mathematical and clinical with a cast of Black actors in a mainstream media environment. This is Hollyweird’s aim— to acknowledge Black popular crossover actors — and keep them isolated from other superb Black actors they might have worked with in theater or those who could actually enable the particular actor’s prowess, together creating something magical, if not brilliant.

You can be too good.

Westworld taps into the actual fantasies of the general mass-market white viewer: alone in the first 49 minutes of the premiere episode (1,1) we see white cowboys kill two men of color: an Indian and a Black man. Callously, simply, with no emotion. I kept waiting for John Wayne to show up. (In season 1, ep. 6 - Thandi Newton is raped within the first ten minutes.) I bring this up to give context: Wright will be framed in these pictures, his talent in these structures. So you have to lower the volume every ten minutes when a shoot-out or violent act is committed, then raise it when Wright or Hopkins have something intelligent to say, and then go back to hiding from the rape and pillage again. This does not make for an invigorating or entertaining TV experience, it is only good for inducing psychosis or anesthetizing an audience. And in such a show, Wright comes off rather hollow to me…like an actor searching for a way through (or out) the screen he is in. Again, unlike his early golden era, his existence now on the screen is particularly maintained and manipulated by producers and directors.

As if from a different era (and confined to such), Wright is an anomaly: a brilliant Black actor who became a Hollywood star, is highly respected by just about everyone, has the chops and gravitas to go head to head with anyone…and yet is perpetually conditioned and “sealed” into a presentation he has no authority over. After 25 years of fame and Hollywood success however shouldn’t that have changed a long time ago?

Answer: No. it hardly changes for ANY Black person who is brilliant in ANY field unless they are independent.

In corporate America, nearly all Black managers have direct reports. And yet most white managers of any tier are rarely curated by anyone. If they have someone to check up on them it’s Human Resources. Blacks must have an overseer: Hollywood will have no problem giving you money (they have never been in fear of Black millionaires) foisting your profile, popularity, and performance-as long as it doesn’t affect their own lives and ethos.

Wright is an arthouse hero and blockbuster actor who should, like Willem Defoe, cast a funky shadow on the assembly and category of movies. But also…he has to want to do so. It does seem, according to recent interviews, that he is pining to return to the stage and trying to make the transition into a new phase. It can’t be easy. But, thankfully, he is doing what is necessary.

I am wondering if Cord Jefferson’s American Fiction - the feature film based on Percival Everett’s satirical masterpiece Erasure, a novel about a writer fed up with the publishing industry’s exploitation of “Black” authors and culture – and the madness it invokes – will be the film I have been waiting to see him in. Directed first time writer-director Cord Jefferson, it debuted at the Toronto International Film Festival this year winning the coveted People’s Choice Awards. It just may help Wright not be erased from the lexicons of aspiring Black Filmmakers. I am in support of ALL artists. But I feel it is important to remember Black artists and entertainers have a duty to themselves. If the white world can give you money, we must always remember: they are not responsible for supporting your soul. Black artists and producers have to be more conscientious, respectful and enabling of each other. If Black Lives Matter – shouldn’t we at least try to reflect that sentiment in our popular arts?

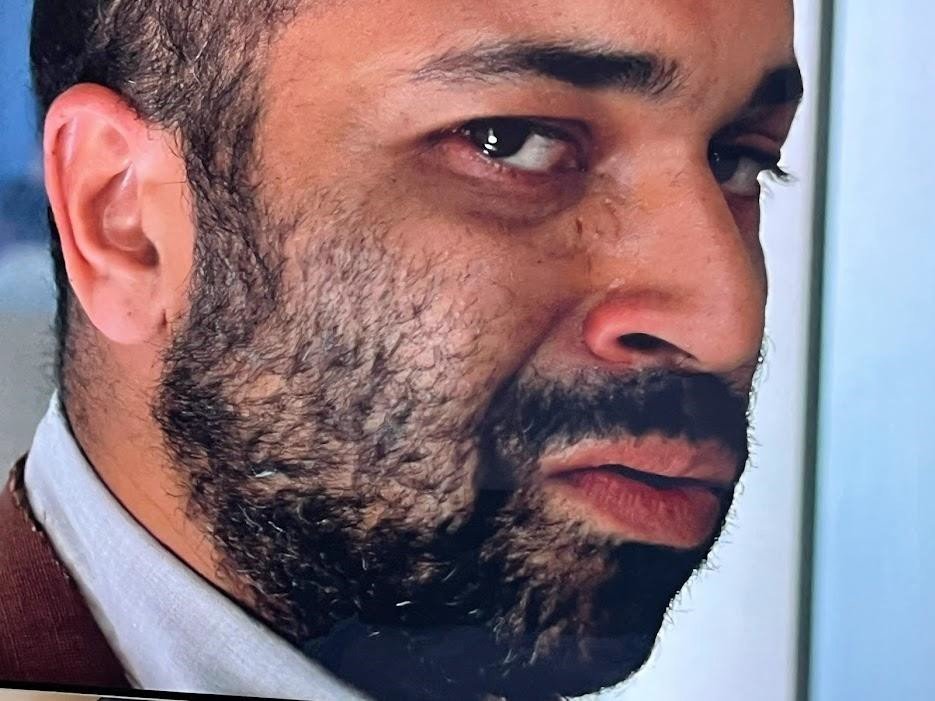

Wright as the tortured Monk Ellison in the eagerly awaited dark comedy, American Fiction by first time director Cord Jefferson. It will be interesting to see if Wright’s penchant for the absurd and droll in Wes Anderson’s films - can make the leap and sing in this funky new Black film that is written by a writer who is worthy of putting words into Wright’s mouth.

Below are eight examples of Wright’s extraordinary acting abilities that I hope will remind filmmakers who have something to say – that brilliance is right there in the center of Hollywood waiting for you…and his name is Jeffrey Wright.

1. Basquiat (Julian Schnabel, 1996)

If he will be remembered for anything, for better or for worse, it is his beautiful performance of Jean Michel-Basquiat, the great New York graffiti artist and modern painter. It was his first lead in a movie. As mentioned in part one of this article, Wright’s seismic power as an actor gave chills and bewitched an entire generation. He was a throwback to the golden age of actors on screen (from Dustin Hoffman in Lenny to Denzel in Cry Freedom!) who created powerful portraits of actual people, but also a dramatically deft interpreter who made an actual life his own. Val Kilmer did it as Jim Morrison, Jamie Foxx as Ray Charles. These are rare instances within the sea of biopics America loves. Method acting is about putting a stamp on something, not being consumed. One consciously goes in…to come out.

On screen, if the artistic interpretation is done well, it is often more truthful than the biography with facts. Actors, artists - should never be concerned with facts. They should be concerned with acts. Truth is what they are after. Not science. The lines may blur, but it is not the job nor interest of an actor to index his work with “what actually happened.” Performing artists can give the truth of a life, not its facts. You don’t watch Alvin Ailey’s Revelations for facts about the trials of Black suffrage down South, you indulge in it and become overwhelmed by its power because it gives truth. And while a husk is real, tangible and a result of living, the artist is responsible for the portrait. In this way one must think of acting more like painting then. How many paintings or drawings of you made you wince when you saw them or intrigued you because you realize these are the feelings and emphasized features you bring out in someone else’s imagination?

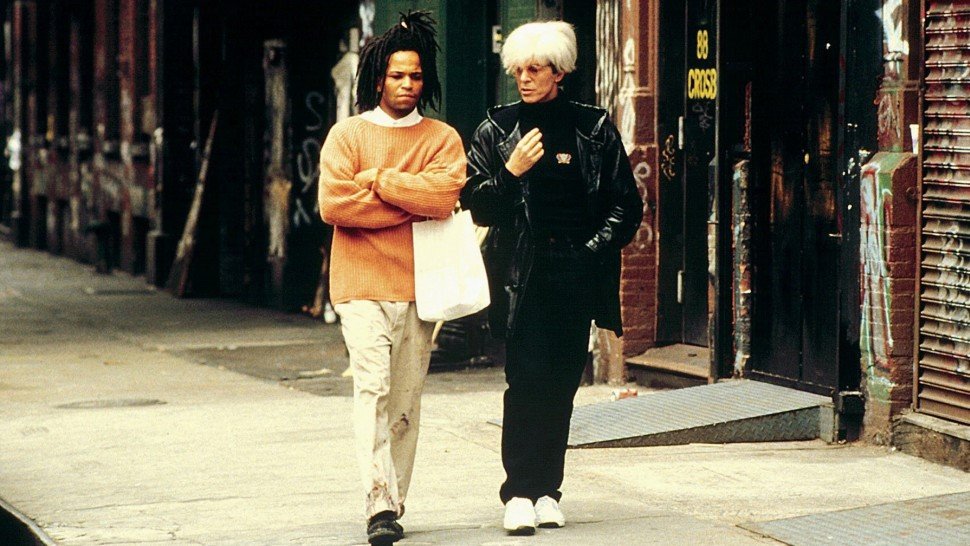

The painter himself, Basquiat, circa 1987

The quickly curtailed criticism that Wright looked nothing like the real man himself took a nose dive when Wright re-defined what it meant to portray someone as an actor might, as opposed to a technical, facsimile machination we were led to believe in as a culture. How many times have you heard someone say “Oh she sounds just like her,” as if mimicry is the defining force of a real person’s interpretation. Mimicry works best in pure fiction actually. It’s a fun and useful technique. Finding where you begin and end with another life however is something else. Having the courage and respect to essentially raise the spirit of the dead is a very scary proposal. Only the courageous make someone else’s life their own. The successful actor makes the “real famous person” themselves. Think about that next time you see a biopic. Because it actually is then more about what the actor reveals than what the movie “says” about the subject. (Frank Serpico once said that Al Pacino was more Serpico than he was. One could say the same about Jeffrey Wright as Basquiat. Somehow, another dimension is relayed.)

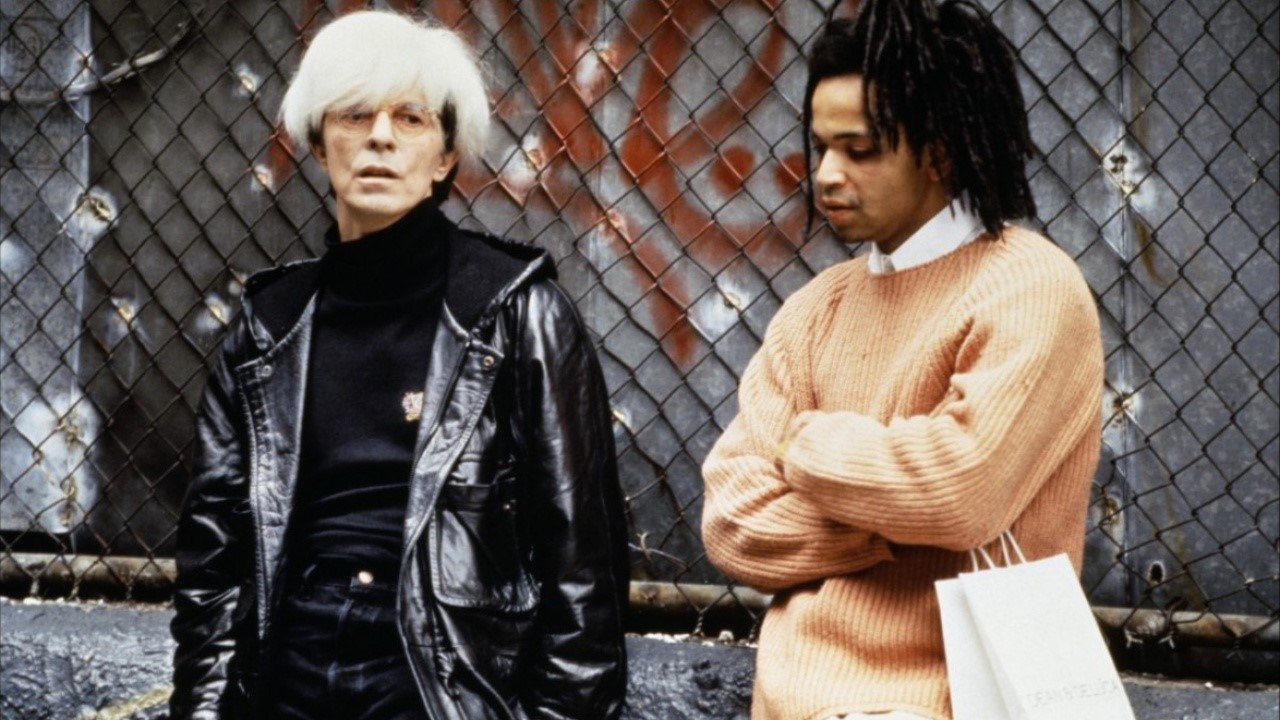

Two forces of Nature: The art-rock icon David Bowie and the young Jeffrey Wright. Says Wright of Bowie: He’s “a singular artist who gives off a lot through his work…There’s also a kind of doppelgänger at work with him: one of the most famous men on the planet playing another.”

Wright’s body language for Basquiat was a reminder that the hallmark of acting is physical. This has been debated for over a century now, but I believe it is true. An entrance, exit - on the stage can express more than an entire monologue. On screen body language (a lost art) becomes lost many times. Instead most actors have guns or phones in their hands, we never even see their fingers or are entranced by a gait. Wright’ folded arms, his tentative stands, his puppy dog look throughout most of the film works because it transmits something. Schnabel, who knew Basquiat tangentially, was conscious enough to shoot and capture Wright’s body when he could. And of course it didn’t matter in the end, for Jeffrey’s eyes, smile and emotional contour of his face was enough that you could just let the camera roll on him. A rare combination, even more rare was the strange collaboration, but the film, which I am extremely critical of for other reasons, became a touchstone of Jeffrey Wright’s talent. Worth repeated watching just for him, Benicio del Toro, and Wright’s funky interactions with none other than the master of strangeness, David Bowie.

Wright’s body language for Basquiat was a reminder that the hallmark of acting is physical. This has been debated for over a century now, but I believe it is true. An entrance, exit - on the stage can express more than an entire monologue. On screen body language (a lost art) becomes lost many times. Instead most actors have guns or phones in their hands, we never even see their fingers or are entranced by a gait. Wright’ folded arms, his tentative stands, his puppy dog look throughout most of the film works because it transmits something. Schnabel, who knew Basquiat tangentially, was conscious enough to shoot and capture Wright’s body when he could. And of course it didn’t matter in the end, for Jeffrey’s eyes, smile and emotional contour of his face was enough that you could just let the camera roll on him. A rare combination, even more rare was the strange collaboration, but the film, which I am extremely critical of for other reasons, became a touchstone of Jeffrey Wright’s talent. Worth repeated watching just for him, Benicio del Toro, and Wright’s funky interactions with none other than the master of strangeness, David Bowie.

2. Ride with the Devil (Ang Lee, 1999)

Ang Lee’s Civil War movie that broached the perspective of the South and the outlaws of the Kansas-Missouri war, Wright is a marvel as Daniel Holt, the Black man who actually aligns himself with the Confederacy. When I first saw the film I was nervous that maybe this was some kind of omen - that Wright would soon become “the establishment’s Black character actor.” The film, like American History X, has an obsession with “dignifying” the white racism of America. But while Lee is not racist himself, the movie is simply weak and at times insufferable, Wright is wonderful as Holt; his “riding with the devil” drawl and thinking are both familiar…and bizarre. Holt must navigate through that complex system and world; ultimately liberating himself – not waiting for the white to do it. Intense role in a shallow movie.

3. Shaft (2000, John Singleton)

John Singleton’s remake with Samuel L. Jackson would have been absolutely nothing without Wright’s almost laissez faire vampiric Peoples Hernandez, the Dominican druglord. Wright is menacing and charming at once, his “too cool” attitude is in full stride in this film because…he basically carries the entire movie. In a role that must have been fun to play, Wright once spoke very candidly about a Dominican supper-club proprietor in midtown named Rafi whom he based the character’s voice and cadence off of. Watch Wright’s meltdown when his brother gets killed…he goes interstellar with rage and it's fun to watch because he is funny, wicked and galvanizing at the same time. Although his introduction scene in jail with Christian Bale does it all for me.

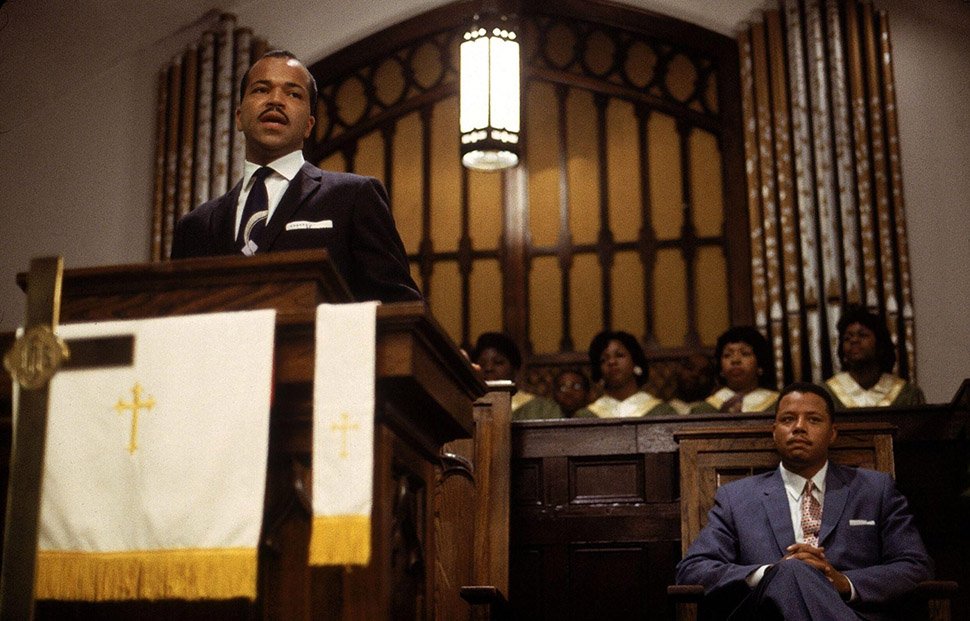

4. Boycott (2001, Clark Johnson)

Wright as MLK preaching with Terrence Howard as Ralph Abernathy

When he was asked to play Martin Luther King Jr., Wright initially balked. What is more interesting however is that he shot the film off the heels of his performance in Julius Caesar where he played an intense Marc Antony who has some of the greatest orations in all of Shakespeare; compelled to meet the challenge - just even technically - of carrying breath and electricity through great speeches, he welcomed the task of MLK. For King himself was Shakespearean. Literally and figuratively. It takes an actor with grandeur to fill his shoes. Wright’s MLK is much more canny and spirited than David Oyewolo’s in the trite Selma and his grounded voice imbues trust and vision. Wright’s MLK doesn’t trust the system and his own attitudes about racism (Wright’s) actually come through his embracement of King’s values and mythology. It mattered none that he has no physical resemblance to the great doctor-minister-activist and it frees the challenge for an actor to tackle the greatest orator of the 20th century by jumping headfirst into his ethos of “content of character,” which should be every actor’s personal affirmation, as if holding a rosary.

5. The Manchurian Candidate (2002, Jonathan Demme)

When Wright goes toe to toe with Denzel in Jonathan Demme’s 2002 remake of The Manchurian Candidate it nearly becomes inspired; Denzel himself (like most actors who have become Hollywood legends) really only digs his heels in when someone is chomping at the bit— or getting close to biting his ass. Screenwriter Maxx Pinkins said to me that “Wright is like Ariel without Prospero. And yet when he has scenes with someone of his caliber or better, he expands on screen.” We discussed his startling performance as the traumatized soldier Al in Manchurian Candidate and how he makes Denzel himself act better, (more vulnerable), and doesn’t miss a beat. By getting into the quarter notes like a jazz musician, he imbues a bit of truth in his own way.

6. Angels in America (2003, Mike Nichols)

With Mary Louise Parker in one of her hallucination sequences; Wright plays an array of absurd characters in “Angels”; his ability to have fun with each of them shines through and lends moments of breathing in between the driven and anxiety-filled Belize.

His Belize in the original Broadway production of Angels caused consternation to director George C. Wolfe who was slightly exasperated by Wright’s slow, searching process (this was an issue originally as well for Schnabel, interestingly enough) but Wolfe certainly must have been proud to eat his own words or gleefully witness Wright’s performance when it went into the universe. Playing Belize was not only one of Wright’s most proudest (and humbling) moments as an actor, it nearly spoiled him into thinking that acting could always have this impact - personally, socially, politically, artistically, culturally…His performance in Topdog/Underdog may have very well even been greater to some – distilling an energy to two lone actors on the stage will definitely reveal everything about their craft and their art and what they must “get off their chest” as Wright once put it.

But on screen, his power, humor, and delicate strangeness comes through like a freight train. I saw Wright play Belize onstage to Ron Leibman and F. Murray Abraham’s extraordinarily absurd and magically gargoyled Roy Cohns. In Nichols deft film adaptation, Wright goes into a darker, more reflective place with Al Pacino’s creepy and mummified Roy Cohn. Outside of Robert De Niro and Joe Pesci, he may very well be the ONLY actor to go eyeball-to-eyeball with Al Pacino – on screen – in the 21st Century. I defy anyone to name another actor at the time who had accomplished this post 1999.

Tony Kushner’s prowess with dialogue becomes incredible music played through the mouths of Pacino and Wright and they perform him well. I only wish August Wilson’s plays would have the same extraordinary engagement that this had in their screen adaptations.

Wright as the sharp and ‘avant’ Belize, the nurse, Al Pacino as the atrocious homophobic gay right-wing lawyer Roy Cohn, who is dying of AIDS. Says Wright: “There were two months when I was working with Pacino during the day on ‘Angels’...working opposite [Pacino], it doesn’t get any better than that. There was an urgency and fierceness about him.”

No stranger to playing the devil, Pacino met his match on screen with Wright who dodged every blow Pacino threw and returned the serve, just as in tennis and equally ferocious. They shared an artistic energy as powerful as any political urge, manifesto, or rebellion. Both obsessed with rehearsals and the repetition aspects of theater, Wright and Pacino soared in this film and both garnered Emmys. The movie itself is great because of their scenes alone. Mike Nichols' brilliance as a director was apparent in that casting choice alone.

Unfortunately, as with all landmark art, Wright’s Belize gave way to dozens of copycats, half-baked stereotypical renditions, and awful cliches around the Black gay man who is “more man than you’ll ever be and more woman than you’ll ever get” as Antonio Fargas’ (cross-dressing Lindy) says in the movie Car Wash.

Wright shared the screen with another giant of the baby boomer method actors, Meryl Streep. Their energy and performances were mutual, but on screen– he gave Streep a run for her money

7. Cadillac Records (2008, Darnell Martin)

Wright’s raunchy debonair and fierce portrayal of the ‘Father of Chicago Blues,’ gave finesse to the raunch and passion of Muddy Waters persona and music. Like Muddy’s playing, Wright kept resorting to the same three or four chords and used them superbly. Virtuosity should never be the key to performance art, conscientious choices should be. How well you play two notes is as important as how broad your language and dynamics are.

Wright as Muddy Waters: It’s a role he was able to bring his innate theatricality and dangerous edge to. His sex appeal and charm in one hand, his sincere rebelliousness and vulnerability in the other. Muddy Waters may not be as impenetrable as Robert Johnson, obviously, but Wright’s performance brings the myth into a tangible human being if only on a screen. Actors enjoy playing musicians the way musicians admire the dramatic precision of actors. Wright’s Muddy may actually be just that in light of Eamonn Walker’s dazzling Howlin’ Wolf, but Wright’s mischievousness cuts through like a knife. He grants the film its gravity (as he does to most movies, even bad ones, seem to benefit from having Wright in them).

Telling the story of Chess Records 1950’s influence, Martin’s film may be heavier on dazzle than dramatic truths (facts are something else), but the film’s mainstream punch at least gave way to some interesting, if sometimes too pitched or pat, performances. The script’s scenes and stale dialogue gets in the way of what may have been a more impactful film at times, but it doesn’t take away from some of the electricity. Even when the flamboyance of the film veers into kitsch. I will look forward to seeing Wright do Muddy Waters as he was before he died at age 68. It would be a fascinating exploration.

8. Boardwalk Empire (2013, HBO series, Howard Korder, writer)

Boardwalk Empire’s best villain and one of its best characters is a man “disemboweled of his moral integrity,” says Wright.

Marginally inspired and based on Casper Holstein, the West Indian Harlem numbers running and ardent philanthropist (he was one of the major fiscal architects and supporters of the Harlem Renaissance, supporting countless artists!) Jeffrey Wright was given the delicious role of Narcisse - an immoral version of the great Holstein - a machiavellian gangster in the excellent Boardwalk Empire series that also gave him and Michael K. Williams as Chalky White (whom Narcisse outmaneuvers and destroys) the opportunity to act together in some powerful scenes.

Ultimately, Wright’s Narcisse, is the perfect nemesis for Nucky Thompson (Steve Buscemi) and the role showcases all of Wright's well-worn talents: it was his best villain since Shaft and by far more complicated.