The Relentless Power & Human Radicalism of Sue Coe

by Dennis Leroy Kangalee

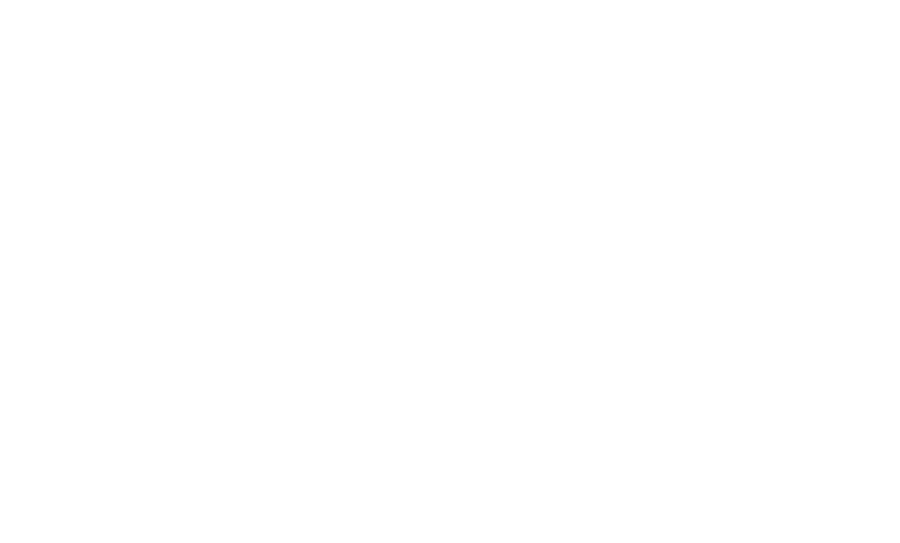

X: Sue Coe and Judith Moore’s sublime collaboration and homage to the spirit of Malcolm X and a declaration against the horrifying capitalist nightmare world we live in…

Nearly five years ago I had re-read Sue Coe and Judith Moore's powerful "Malcolm X" book. And then in August of 2018, I was intrepid to seek out where her works were stored and who represented them. Just a mere glimpse at her artwork on display that summer at the Galerie St. Etienne’s (“Recent Acquisitions,” exhibit July 17-October 19, 2018) and one’s senses were not only fully restored, but morally recalibrated.

The ‘consciousness’ compass finds it north and gravity is once again restored. You know where you are, where you are going. And this is as true for the world outside as it may be for your own inner proclivities. You understand your own rage and exasperation at our society and your disappointment and shame at our 21st Century spectacle is not only affirmed but somehow galvanized so intensely – and simply – that you can’t but help regard the social and political messages of Sue Coe’s artwork as being almost biblical if not tragically visionary because there is something terribly perennial and contemporary about them and it disturbs as much as it comforts. It comforts because it assures you that you, as a radical humanist – as a thinking feeling person – are not alone in the prison we inhabit, the one the Establishment seeks to pathologize and render insane.

Unless of course you are a celebrity or have the money to be allowed to say how you feel. Rich enough to not only own property, but your emotions – as well as the thoughts in your head.

This is what is so dangerous, subversive, and beautiful about the wide ranging fury of white British artist Sue Coe’s artwork.

While protest art has struggled in various mediums and throughout many decades, it never let up in Coe's case. Her overwhelming body of work included in “Graphic Resistance” at MoMA P.S.1 in September 2018 reminded me of the perennial reach of her cry. And this was all precisely as Donald Trump climbed the halls of vulgarity and despicability and less than two years before the pandemic hit.

This overview of her work includes classics such as the chilling 1983 mural “Woman Walks Into Bar – Is Raped By Four Men on The Pool Table – While 20 Watch.” Conjoined with material from recent sketchbooks, one can trace the evolution of her work, the nuances of her style – whether drawings or mixed media, etc. – but as Holland Cotter pointed out in the New York Times, Coe’s “ethical mission of art” has not changed or altered. It has metastasized and continues to challenge the times and we are all better for it.

I hope budding feminists and political artists learn from her, but more so -- be inspired by her. A glance at virtually any of the art works by Coe hanging on the walls at Etienne is not only worth more than a two-hour sitting of any of today’s so-called “political” films, but far more human, empathetic, angry, insightful, haunting, and profound. Writer-critic Hilton Als, in either a psychotic state or a result of having taken TOO MUCH medication, declared Sam Shepard to be America’s greatest “Hip Hop” playwright after Amiri Baraka in 2018. To this day I have no clue what that means, and forget the fact that it is insulting and disparaging to Baraka’s entire legacy – it renders hip hop’s socially conscious thrust hollow and it categorizes Shephard in a genre he was never consciously part of or an adherent to - especially not in an aggressive political way – which is at the root of hip hop (and punk rock) to be precise. Hip hop is as moribund as almost anything else is now. I wonder why Hilton Als felt the need to celebrate Shepard and patronize his Black readers of The New Yorker? While Shepard commented on American society, no one in their right mind would equate him in the same breath as Amiri Baraka – when it has never been any secret what, how, or why Baraka wrote and felt and thought the way he did or what his aims were: to blend racism and capitalism into a cocktail and set the whole thing on fire – if he couldn’t drain it from below, like some massive ocean going down a vent…

If Als had wanted to champion another contemporary artist on par with Baraka’s transcending radicalism and horrifying vision of Western society and capitalism – he’d have mentioned Sue Coe. An artist who is to fine art what Brecht was to the theater; what Amiri Baraka was to poetry and drama. But most men, regardless of their sexual preferences or identities, have a problem enabling the works of women that's as tough and bold and beautiful as men's own. New York critics will champion Jane Fonda, but seldom talk about the impact of a theater director like Judith Malina. Or the extraordinary rancor of Julie Dash's early work.

If American film directors could make their live action political cartoons as coarse, immediate, and stately as Coe does – they'd achieve something as a director that the popular masses need: an artistic vitriol that is born out of both the spleen and the heart. In fact, I’d go as far to say that there is no contemporary Western filmmaker who makes “protest” movies as honest and as righteous as Sue Coe makes her artwork.

And the answer is simple.

Because Coe not only believes wholeheartedly in what she is saying, she offers us artwork like a sacrificial lamb we’re afraid to touch; there is a delicacy, urgency, and shame that arises when one sees her work and it puts the viewer in the center of the dilemma of being in a Capitalist/Racist/Oppressive society and being in the center of a drama or piece of history that is eternal, that is always NOW. And it’s not calculated, it comes off as a matter of fact, a case of just “how things are”…and may always be.

There is nothing self-congratulatory about her art, nothing ironic or “knowing” in the sense that there is with most Hollywood or Sundance Film Festival’s “message movies” or political grandstanding. And it is particularly glaring when we consider the fact that most “agitprop” films being financed by the studios are helmed by Black directors…who are not from any Leftist organization from below, do not possess a personal ideology that is anti-spectacle, or anti-capitalist.

They are members of the ‘Black Bourgeoisie’ and they are doing us all a huge disservice.

“All Good Art is Political,” as the Etienne named one of its shows which conjugated Sue Coe with Kathe Kollwitz [German, 1867-1945] (one of Coe’s own inspirations and an artist’s work who led Coe to seek out the St. Galerie Etienne herself). The program note from 2017 opens with a quote by Toni Morrison on the nature of art being inherently political, because it is secular and has to do with the here and now and being in and of this world. And this is true whether the work screams and spits (The Sex Pistols, the Living Theater, the Black Arts Movement, Public Enemy) or whether it is tempered through a less vitriolic filter (Gil Scott Heron, Curtis Mayfield to Pink Floyd to, hell, even the humanist films of Frank Capra!)

Everything is political and everything is personal. The personal is political…there is no such thing as “only business” and certainly no real foundation for the claim that art or entertainment can be devoid of political and social meaning. To determine the legitimacy of “political art” one could look at how the work was made, what led the artist to arrive at his or her final subject or form but honestly that itself could lead to too many academic booby traps and intellectual trapdoors, setting us off on a path that quickly becomes pretentious and deeply fraudulent.

A cynic – a person resisting the deeper and more nuanced aspects of political art would declare, “What’s the big deal? If such and such director wants to make a statement – why can’t he? Why do you care?”

I don’t mind that film production companies and their movies want to comment on our racial zeitgeist. I welcome statements against racism, but a work of art has to go beyond a placard. What are you saying a slogan can't? Most "socially conscious" movies are bad. Especially the ones that pretend to be “angry.” Those are bullets wrapped in sugar. I dislike bad art, but worse - I dislike people who create art about racism simply to improve their own status within it.

When I look at Sue Coe’s artwork she does what modern popular American “social justice” filmmakers CLAIM to do: she equates capitalism with racism and she spits at them both, unleashing tempestuous nightmares that have the power and immediacy of a Goya painting.

And this – all – from an Anglo woman who empathizes so much with her subjects/theme’s pain – that you wonder how the media she creates doesn’t either implode, curl at the corners to hide away…or just wither under the weight of its own pain.

The real question here is why more women, in particular, aren’t looking at the work of Coe instead of fawning over establishment fine artists like Kara Wheeler (who gives the guilty white liberals every stereotype and fetish they desire) or “strong” rightwing neo-liberal movie directors like Kathryn Bigelow (Hurt Locker, Zero Dark Thirty) whose movies are just commercials for the United States government.

Conceptually, Sue Coe achieves what the French writer & actor Antonin Artaud (“Theater of Cruelty”) challenged theater artists to do in the 1930’s: make the spectator and performer one, expressing their angst with the draconian sweep of a plague. Artaud was convinced if the audience felt the pain of the oppressed – they would be moved to eradicate it. Like Amiri Baraka wrote and the Living Theater performed, Coe brings a fury to her stage by any means necessary. Which naturally leads us to Malcolm X.

At the Left is the cover of Sue Coe’s 1986 series “X” and the subject of her first exhibition at PS 1 in 1986. These works seems to hover and cast a large shadow over her entire oeuvre, for as varied and far reaching her body of work is – to me it can all be summed up in the “Malcolm X” series she has created which I believe crystallizes Coe’s own vision of the world we live in – from the atrocities we commit in capitalism’s name (torture, racism, sexism, abuse of animals, imperialism, etc.) to the wars we sanction within ourselves and against our own conscience.

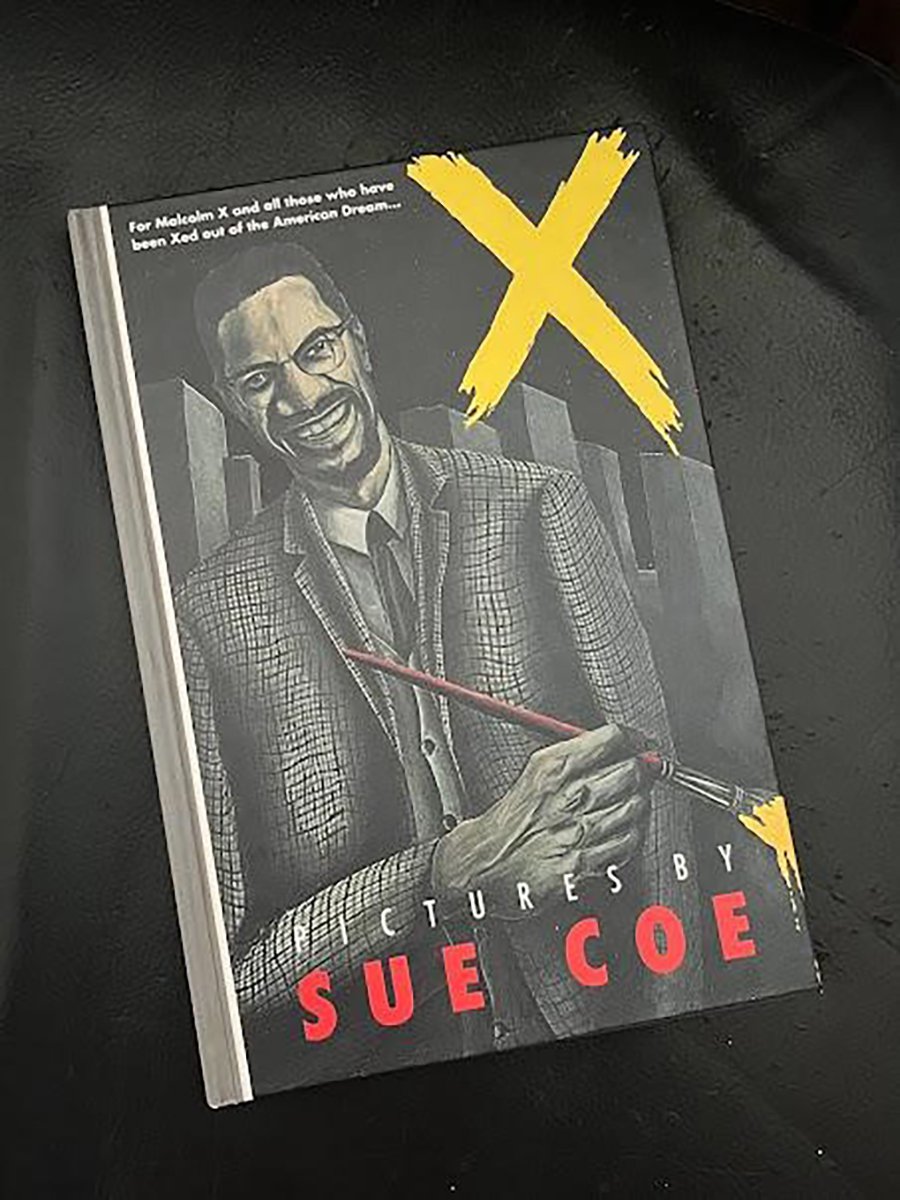

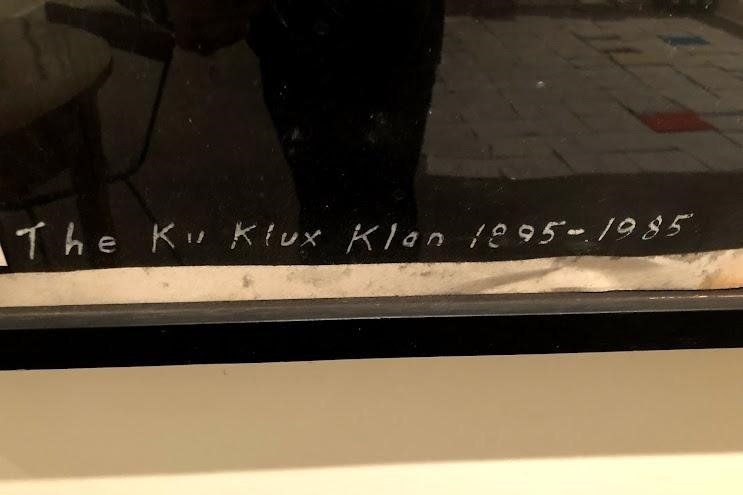

Two large-scale works from this “Malcolm X” series hang powerfully, yet humbly, at the Galerie St. Etienne – reminding you of the full force of Coe’s vision and heartbreak she renders through her cosmic illuminations of Malcolm X’s mother, the KKK, and the staunch reminders of what Malcolm X preached, warned, and felt. Her “Ku Klux Klan, 1895-1985” powerfully implements Malcolm’s damning words on capitalism in red along the upper margins of a hideous image of the KKK torturing and roasting a Black man to his death.

The deep, murky, vinyl liquid darkness of her Malcolm X series in particular resonates because it seems to be a portrait of the state of being of our world, in constant de-evolution, like a spinning wheel thrusting backwards upon a podium gathering more and more speed – and yet remaining in place.

The oddity of a treadmill spiraling with no one on it in the dark is a good analogy. Even the sound of the rubber would creep you out. And it is part of this immaculate “senses-engaging" that Coe’s work seems to have. It hijacks your senses and instantly asks you to admit things to yourself, the world you live in, and the part you play in that world. It’s the reflection that makes it art. Without that, such creative acts are mere “entertainment” or propaganda. And bad propaganda at that. It’s a pity that Mao was correct: “All art is propaganda. But not all propaganda is art.”

Sue Coe’s art in this moment should be seen as a reminder, a standard which to judge other “political” or “revolutionary” works of art and, in particular now, Hollywood movies that attempt to co-opt and derail real radical artistic work with liberal platitudes, millennial complaining, and snowflake social justice that melts as soon as it hits the ground.

While Sue Coe’s work may not continue to gain any commercial awards or be on any of the Buzz feed radars along with the newly appointed harbingers of the so-called Revolution that seems to be taking place solely between various bank accounts, it will humble and decimate any attitude, artwork, or stands that claims it is part of a “resistance.” For, if anything, Coe doesn’t necessarily resist the status quo or the world’s problems. She aggressively engages them and takes no prisoners. If she does anything – she welcomes…by defying. The first lesson in creating not only worthwhile agitprop, but art that will remain relevant because of the sheer velocity of its passion and outrage.

In 2021, the Galerie St. Etienne closed its exhibition space and became an art advisory. The gallery’s library, archives and educational activities were taken over by the Kallir Research Institute.

Below are snapshots I took of Sue Coe’s artwork on the walls of the Galerie St. Etienne in 2018, my favorite hang out before the pandemic. (24 West 57th Street, NY 10019).

Done the same year as her superb Malcolm X book with poet Judith Moore, Sue Coe’s phantasmagoric KKK piece - on the wall of the Galerie St. Etienne…In person it is stunning as it is provocative.

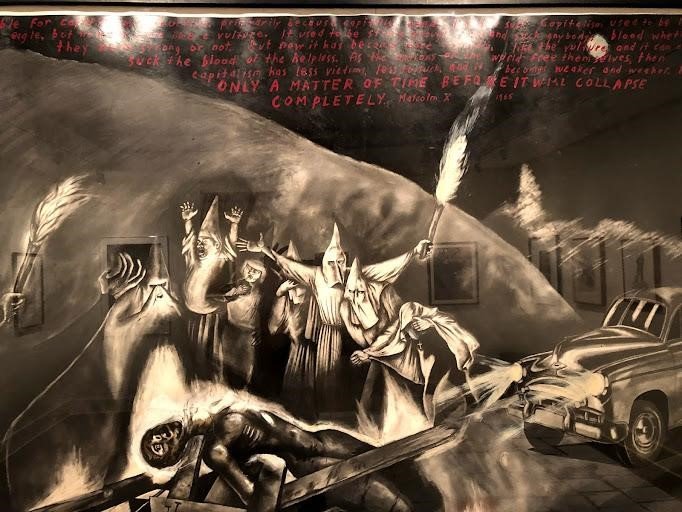

Notice the 1965 Malcolm X quote in red ink…Coe’s untitled phantasmagoric KKK nightmare was inspired by an actual incident, of which she pasted a photograph of one of the investigators at the actual site of the Klan’s 1985 brutal murder of a Black man:

Judith Moore’s visceral poetry (yellow scrawl) complements Coe’s sublimely savage artwork

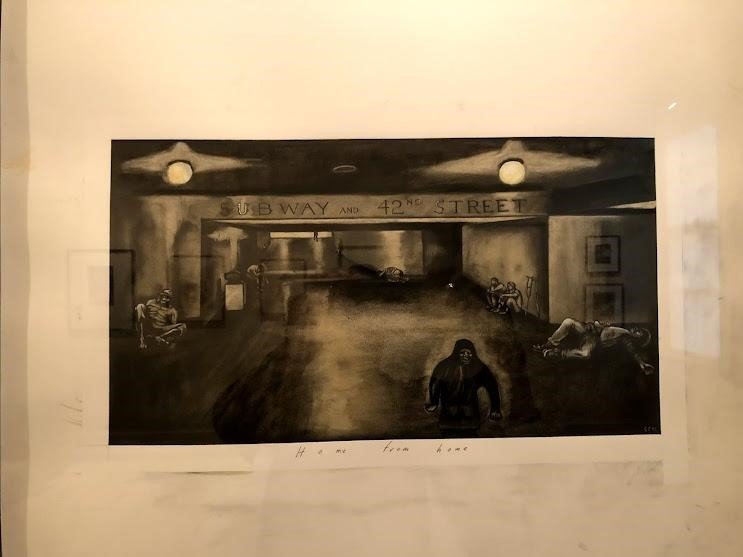

Coe’s “Home From Home,” just one of several powerful artworks dealing with homelessness.

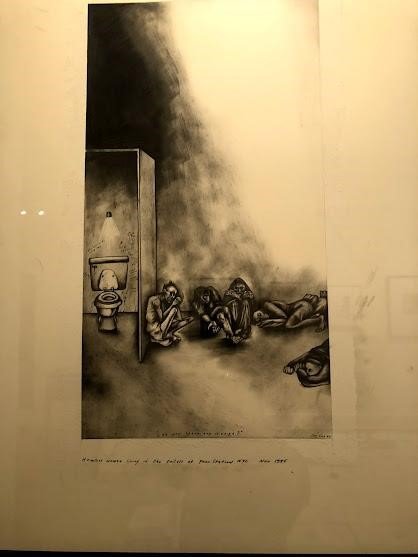

Coe’s Homeless Woman in Penn Station…

Coe’s pro-union agit-prop Strike painting, with bold pop art colors

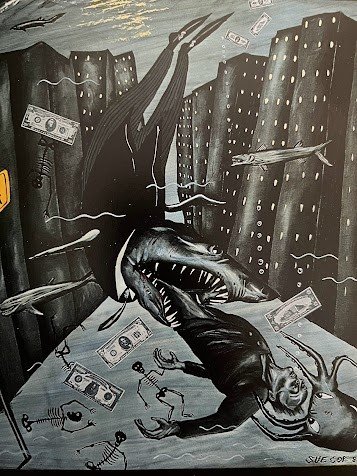

Demonstrative displays of the vulgarity and cruelty of capitalism abound in Coe’s work. She’s as subtle as a…shark. And this, like Flamenco dancing or the verses of Gwendolyn Brooks or Charles Bukowski - exists to keep the fire in your belly. Her art is not “birdbath” poetry, it is a cosmic reflection and reminder of what we must contend with…or be careful of.

Malcolm’s murder. Powerful. The psychotic bleakness. The grimness of it all, we become pallbearers not by choice, but by proxy. We witness what she does. We all have a responsibility. In Coe’s world, however, once in…it’s hard to get out. This image, along with her freakish Klan images, to me is the true “American Gothic”.